生物多样性是生态系统生产力、稳定性、可入侵性以及营养动态的主要决定因素(Hooper et al., 2005)。在生物群落中, 所有物种均与其他物种直接或间接相互作用。种间相互作用(简称种间互作)是实现生态系统功能和服务的基础, 包括物质循环、传粉、种子传播、生物控制等(Bascompte & Jordano, 2007)。例如, 植物与传粉者互作有助于实现植物繁殖的成功(Fründ et al., 2013), 植物与种子扩散者之间的互作有助于实现种子扩散和幼苗更新(Farwig & Berens, 2012), 而鸟类取食昆虫有助于生物防治(Morante-Filho et al., 2016)等。因此, 种间互作在生物多样性及其生态系统功能与服务的形成、维持等方面发挥了十分重要的作用。在生态群落或生态系统中, 以物种为节点, 相互作用为连接, 形成的复杂的网状结构为种间互作网络。近年来, 种间互作网络的研究成为生物多样性与生态系统功能研究的前沿领域。从生物多样性到生态系统功能的实现可分为以下几个过程: 基于环境筛选作用的生态群落构建、群落内的种间互作网络的形成、种间互作提供的生态系统功能(Schleuning et al., 2015)。目前, 生态学家通过运用网络理论和方法来重点关注群落内物种、功能群或营养级水平之间的相互作用如何影响生物多样性以及生态系统功能或过程, 从而阐明群落结构与功能、多样性与稳定性维持的生态和进化机制。

食物网是描述生物群落内物种间“谁吃谁”的关系网, 其结构如何影响群落的稳定性是群落生态学中的一个经典命题。自May (1973)在20世纪70年代的先驱性工作以来, 理论生态学一直在探究影响群落稳定性的条件。例如, 用捕食者-猎物相互作用模型研究相互作用强度、弱相互作用、杂食性、体型比例以及生物异速生长在稳定性中的作用。近30年来, 食物网的研究范围已有深度的拓展, 特别是互惠网络研究使这一领域得到了快速发展。互惠网络指的是发生互作的物种都在互作过程中获利。如传粉网络, 传粉者与植物都在互作过程中获利, 传粉者获得报酬(花粉或花蜜), 而植物则实现了传粉。目前, 种间互作网络的概念已经突破了传统食物网的范畴, 种间互作网络可作为生态系统中生命有机体间相互作用的一种表现。这些相互作用可以是营养的, 也可以是非营养的, 包括拮抗关系(如捕食等), 互惠关系(如传粉、种子传播等), 竞争, 偏害共栖和共生等类型。除传统食物网之外, 任何一个由两类物种发生种间互作所形成的互作网络均为二分网络, 是近30年来种间互作网络研究的重要内容。由于物种之间的营养关系直接影响到物质和能量在生态系统不同组分之间的流动和循环, 故网络结构与生态系统功能密切相关。即使群落具有完全相同的物种多样性, 但如果网络结构不同, 生态系统功能也可能存在差别。因此, 种间互作网络研究架起了连接生态系统生态学和群落生态学之间的桥梁。

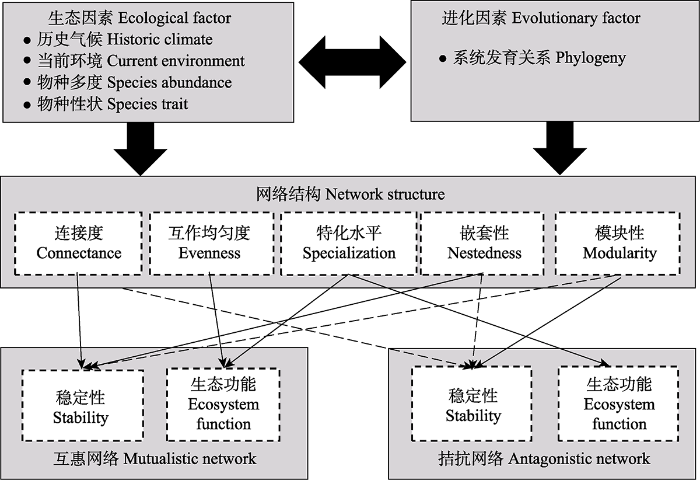

当前种间互作网络的研究主要包括其拓扑结构的描述、网络的构建机制及种间互作网络结构的功能和稳定性等方面。尽管种间互作网络是近年来群落生态学和生态系统生态学的研究热点, 但国内有关种间互作网络的研究尚处于起步阶段, 尤其是实证方面的研究。目前, 我国基于实证的种间互作网络研究主要涉及网络拓扑结构的描述(Sanitjan & Chen, 2009; Fang & Huang, 2012; 郭彦林等, 2012; Zhao et al., 2016, 2019; Zhang & He, 2017), 种间互作网络构建的影响因素(Zhao et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2018)等, 但对种间互作网络结构与功能和稳定性关系的相关研究极少。在群落及生态系统水平上开展种间互作网络研究将为群落的构建机制、物种间协同进化、物种性状分化、生物多样性维持和生态系统稳定性等领域提供新的视野。因此, 本文从种间互作网络的结构特征、构建机制、稳定性机制、生态系统功能维持等方面综述当前国际网络生态学研究中的热点问题(图1)。

图1

图1

物种间互作网络的结构、生态系统功能和稳定性的关系。

Fig. 1

Structures (and their determinants), ecosystem function and stability in species interaction networks.

1 种间互作网络的结构特征

传统的网络结构特征研究历经文字描述、概念图解、特征参数描述、定量分析等阶段。种间互作网络常包括定性网络和定量网络两个大类。其中, 定性网络, 又称为未加权网络, 是指当物种之间存在相互作用时连接为1, 而没有相互作用时连接为0; 而定量网络, 也称为加权网络, 是指通过种间互作的强度来表征连接强度。

早期对种间互作网络结构特征的描述仅限于一些简单的指数, 如连接数分布及连接度等(Jordano et al., 2003)。连接数分布指的是物种连接数的频率分布, 常见的分布形式包括指数分布、幂律分布及指数截断的幂律分布等。连接度指的是所观测到的连接数占潜在的连接数的比例, 通常用来描述网络的泛化水平及冗余程度, 连接度越高说明网络越泛化, 功能越冗余。然而, 连接度对网络大小和取样强度敏感, 因此用连接度指示网络结构和群落稳定性存在一定的局限性。随着研究的深入, 新的结构指数引入到互作网络研究中, 例如嵌套结构及模块结构等(Bascompte et al., 2003; Olesen et al., 2007)。嵌套结构通常是互惠网络的一个特点, 在嵌套的互作网络中, 特化物种的互作物种是泛化种互作物种的子集(Bascompte et al., 2003)。嵌套是一种不对称特化的特定类型, 具有中心域与非对称性两个重要特征。嵌套结构中心域内泛化物种间形成密集的连接。嵌套结构的非对称性表现为网络中的每个物种与其他物种之间的连接数差异较大, 以及网络中特化种趋于与泛化种相互作用而不是与特化种相互作用。模块性是互作网络的另一个重要特性, 即模块内部物种连接紧密, 而模块间的物种连接较为松散(Olesen et al., 2007)。拮抗网络通常呈现一定的模块结构, 但每个模块内部仍常具有一定程度的嵌套性(Kondoh et al., 2010)。

表1 二分网络结构指数

Table 1

| 水平 Level | 结构指数和解释 Structure indices and explanation | |

|---|---|---|

| 物种水平 Species level | 物种连接数 Species degree | 网络中某物种与其他营养级物种发生联系的数量 The number of interacting partners |

| 物种强度 Species strength | 指某一个动物或植物物种对植物或动物物种的依赖度或所受作用强度的总和。 The sum of dependences or interaction strengths of the animals on a specific plant species, or the sum of dependences of the plants on a specific animal species. | |

| 嵌套等级 Nested rank | 指在一个网络嵌套矩阵中所处的等级; 数值越低, 表示该物种更为泛化, 反之亦然。 Which is measured as the position in the nestedness matrix. A generalist will interact with more species and thus have a rank closer to 1, while specialists will have ranks with higher values. | |

| 特化指数 Specialization index | 用来衡量物种的特化程度的指数(0-1) Assesses the specialization of a species (ranging from 0 to 1) | |

| 连接多样性 Partner diversity | 某一物种的连接伙伴的Shannon多样性, 用于衡量物种的泛化程度。 Shannon diversity of the interacting partners of each species, which indicating generalization of a species. | |

| 网络水平 Network level | 连接度 Connectance | 网络中实际连接数与潜在连接数的比值 The proportion of potential links that are actually realized |

| 物种平均连接数 Links per species | 网络中连接数与物种丰富度的比值 The average links per species | |

| 嵌套性 Nestedness | 在嵌套的互作网络中, 与特化物种相互作用的物种是与泛化物种相互作用的物种的子集。 A pattern of interaction in which specialists interact with species that form perfect subsets of the species with which generalists interact. | |

| 模块性 Modularity | 互作网络中一些物种通过连接会构成模块, 模块内部的物种间连接相对紧密, 而与模块外的物种连接较为松散。 A pattern which occurs when the species form cohesive subgroups (modules), such that species within a module interact more among themselves than with those of other modules. | |

| 互作强度的非对称性 Interaction strength asymmetry | 网络中发生互作关系的物种之间受影响程度的差异性 式中, Explaining dependence asymmetry across both trophic levels. | |

2 构建机制

研究物种间互作网络的构建机制能够为全面揭示生物多样性的形成和维持机制提供新视角。阐明群落内种间互作及互作网络结构是随机发生还是由一系列生态和进化因素所决定是种间互作网络构建机制的关键问题(Bascompte & Jordano, 2013)。现实中, 任何一个种间互作网络结构可表达为包含多种影响因素的一个函数(图1), 如物种特征、中性和扩散过程, 以及由此产生的物种时空分布格局、群落结构(物种丰富度、组成和多度)和取样效应等(Vázquez et al., 2009a, 2009b)。基于不同因素影响的比较研究结果, 形成了种间互作网络构建机制的不同假说, 主要包括中性假说(neutral hypothesis)、限制性连接假说(forbidden links hypothesis)以及亲缘关系假说(phylogenetic-related hypothesis)等(表2)。中性假说认为群落内个体间的互作是随机的, 因此种间互作的发生概率受到物种多度的影响。而限制性连接假说则认为物种在时空匹配的前提下, 互作仅在种间形态或生理上相互匹配才会发生, 因此种间互作受到物种分布、物候、形态和生理等功能属性的限制(Jordano et al., 2003)。亲缘关系假说认为近缘种往往具有相似的形态、物候、分布等特征, 因此近缘种由于系统发育限制在网络中有相似的相互作用从而扮演相似的角色(Olesen et al., 2007)。

表2 种间互作网络构建的主要假说

Table 2

| 假说 Hypothesis | 解释 Explanation |

|---|---|

| 中性假说 Neutral hypothesis | 群落中个体之间的互作是随机的, 因此多度越高的物种与其他物种发生互作的概率越高 Which assumes that individuals interact randomly, thus network interaction patterns are mainly dependent on species abundances; that is, abundant species interact more frequently and with more species than rare species |

| 限制性连接假说 Forbidden links hypothesis | 物种间互作的发生受限于物种间的时空分布, 以及物种特征的耦合度 Pairwise interactions that are impossible to occur owing to temporal-spatial or species traits mismatch |

| 亲缘关系假说 Phylogenetic-related hypothesis | 亲缘关系近的物种在互作网络中扮演相似的角色 Tendency of phylogenetically similar species to have similar roles in interaction network |

2.1 物种多度

物种多度对种间相互作用及网络结构有重要影响, 如群落中的优势种比稀有种具有更多与之互作的物种(Vázquez et al., 2009b)。在群落中, 物种多度分布表现为大部分物种多度很低, 仅有小部分物种多度很高, 呈对数正态分布。根据中性假说, 种群数量大的物种与其他物种相遇以及发生互作的概率要高于种群数量小的稀有物种, 导致多度高的物种能够与更多种类与数量的物种互作, 而多度低的物种趋于与多度高的物种互作, 形成非对称性和嵌套性网络结构(Bascompte et al., 2003; Fontaine, 2013)。研究表明, 在一些互惠网络中, 仅用多度就能解释网络的连接数分布、嵌套结构、连接数及连接强度不对称性等网络结构特征(Vázquez et al., 2009a)。

研究表明网络结构也是群落中物种多度格局形成和维持的驱动力之一(Fort et al., 2016)。因此, 研究物种多度和种间互作网络结构关系需要同时考虑: 物种多度(或群落组成)是否以及如何影响种间互作, 以及种间互作和网络结构如何影响群落物种多度(或生物多样性)(Bascompte & Jordano, 2013)。如果物种多度能够影响网络结构, 形成新的网络结构亦能反作用于物种多度(反馈作用), 那么如何解决这个“鸡生蛋还是蛋生鸡”的循环性问题? Dormann等(2017)对此提出了几个判定多度驱动还是结构驱动的假说。首先, 当种群大小和其活动节律主要受环境(如巢穴和极端温度)决定时, 物种多度驱动网络结构。当种间互作高度特化时, 网络结构会驱动物种多度格局的形成。因此, 物种多度作为驱动因素可能更适合于以种子传播网络为代表的泛化食物网(Schleuning et al., 2011), 而不适合于高度特化的宿主-拟寄生者互作网络(Maunsell et al., 2015)。其次, 在研究多度和食物网结构时同样还涉及以下两个方面的机制: 其一是生态学上的取样效应, 因为优势种通常更为泛化, 具有较多与之随机互作的物种(Fort et al., 2016)。其二是观测上的取样效应, 因为优势种通常比稀有种具有更多的观测数, 使得稀有种更易受到取样的限制(Dormann et al., 2017)。尽管这两种取样效应在实际研究中难以区分, 但在解释上却完全不同, 应尽量予以区分(Blüthgen et al., 2008)。

2.2 物种性状和时空耦合

研究发现, 仅用物种多度并不能完全解释某些群落中种间互作的模式以及所形成的网络结构, 因为种间互作还受到物种间时空分布和性状匹配的影响。 如果物种的物候和分布存在差异, 或互作双方性状不匹配, 尽管物种多度很高, 仍不能发生相互作用, 即形成了限制性连接(Jordano et al., 2003; Olesen et al., 2011)。例如, 性状匹配程度决定了植物与蜂鸟相互作用的强度(Maglianesi et al., 2014)。Vizentin-Bugoni等(2014)通过独立采样控制物种多度, 发现限制性连接的影响强于多度的影响。因此, 群落中互作物种的功能多样性也是种间互作网络构建的驱动力(Albrecht et al., 2018)。植物-传粉者之间性状匹配的假说认为, 只有当传粉者口器的长度等于或大于花粉管的长度时才会发生相互作用, 故形态学上的限制性连接表现为短口器传粉者不能取食长管花植物的花蜜并为其传粉(Stang et al., 2009; Vizentin-Bugoni et al., 2014; Sazatornil et al., 2016)。研究表明, 性状匹配可发生在不同类型的种间互作网络中, 从互惠的传粉网络、种子传播网络到拮抗的捕食者-猎物、寄生物-宿主互作网络(Eklof et al., 2013)。然而, 限制性连接和取样不足导致的缺失连接在实际研究中仍难以完全区分开来(Fründ et al., 2016; Jordano, 2016)。

2.3 进化因素

进化和生态过程共同塑造了复杂的种间互作关系及其所形成的互作网络结构(Olesen et al., 2007)。如上所述, 形态、物候、地理分布等物种特征会影响种间相互作用, 而这些物种特征通常具有系统发育相关性, 因此种间互作网络结构同样会受到物种进化历史(即系统发育)的影响(Rezende et al., 2007; Peralta, 2016; Volf et al., 2017)。种间互作网络描述了物种间当前相互作用的模式, 即过去的进化事件对种间互作的塑造可表现为当前网络中物种互作具有系统发育信号(Rezende et al., 2009)。系统发育信号可能来源于两个方面: 第一是物种间互作模式在长期的历史进化生态事件中得以保留, 使得物种互作具有系统发育信号; 第二是当前生态因素会筛选具有相似生态特征的物种, 从而使得群落中物种互作具有系统发育信号(Thompson, 2005; Vázquez et al., 2009b)。由于系统发育限制, 近缘种在网络中有相似的相互作用, 并扮演相似的角色。例如, 系统发育关系较近的物种倾向于拥有同样的连接数, 但互作强度可能不同(Rezende et al., 2007), 而种间互作网络模块内部由近缘物种所组成, 且模块内的物种趋于拥有相似的性状(Dupont & Olesen, 2009; Donatti et al., 2011; Poulin, 2013)。在同一个互作网络里, 营养级间的系统发育信号通常都具有不对称性(Bergamini et al., 2017)。例如, 以捕食者-猎物为代表的拮抗网络中, 低营养级物种(猎物)的系统发育信号常高于高营养级物种(捕食者)。这是因为捕食者趋于捕食具有相似性状的、亲缘关系较近的猎物, 而近缘的捕食者之间的种间竞争会导致它们趋于捕食不同的物种(Rezende et al., 2009)。然而, 并非所有的种间互作网络都具有系统发育信号。如Schleuning等(2014)通过对种子传播网络研究发现, 尽管物种的模块角色在系统发育上也是保守的, 但是系统发育关系并不能完全解释模块性, 而季节性气候则能够更好地预测网络的模块性。

总之, 上述不同因素间存在着复杂的关系, 并以多种方式影响网络结构。有关网络构建假说并非是相互排斥或相互独立的, 而是互补或共同作用于种间互作网络的构建。除了上述的因素之外, 种间互作网络还受到其他因素的影响。例如, 模块和嵌套可能与群落的稳定性和抵御气候变化等干扰的能力有关, 故历史气候波动可能会影响模块性和嵌套性。Dalsgaard等(2013)利用全球传粉网络数据的研究表明, 在传粉网络的模块和嵌套结构形成方面, 历史气候变化与当前气候同等重要。取样效应对研究和推断网络结构也有较大影响, 在网络构建中应该予以考虑(Fründ et al., 2016; Jordano, 2016)。系统发育信号本身往往无法推断出网络构建和种间互作模式的潜在机制。因此, 如何解析系统发育和其他生态因子对网络构建和物种相互作用的影响, 是一个值得关注的方向(Dehling, 2018)。

3 稳定性机制

解析种间互作网络结构如何影响群落稳定性是生态学研究的热点问题之一。网络分析的重要性在于其能辨析种间互作网络的哪些结构特征在应对各种自然和人为干扰因子时发挥何种作用, 从而揭示和预测群落结构与功能、多样性与稳定性之间的关系。有关群落多样性、复杂性与稳定性关系的争论由来已久(May, 1972; McCann, 2000)。基于经验证据, Odum (1953)、 MacArthur (1955)和Elton (1958)认为复杂的群落比简单的群落更稳定, 即认为复杂性会导致稳定性。而May (1972, 1973)通过对随机组合的竞争性群落结构进行稳定性分析, 发现稳定性随复杂性增加而降低; 且当物种数、连接度或相互作用强度增加超过某一临界值时, 生态系统会变得不稳定。此后基于捕食者-猎物网以及竞争性群落中的复杂性和稳定性关系受到了极大的关注。然而, 一个复杂的群落, 根据理论推导是不稳定的, 却能够在现实中持续存在。围绕如何解决理论和现实之间的矛盾是生态学领域一个悬而未决的重大课题。事实上, 如前文所述, 种间互作网络(或食物网)的构建是非随机的, 而正是这些非随机性可以促进物种在群落中持续存在(Thébault & Fontaine, 2010; Stouffer & Bascompte, 2011)。因此在探究种间互作网络结构、复杂性和稳定性的关系时应该充分考虑这些非随机性。

3.1 种间互作网络结构与稳定性

研究群落结构和稳定性之间的关系往往因使用的稳定性概念差异和测度不同而不同。常见的稳定性概念包括抵抗力、恢复力、脆弱性和稳健性等(McCann, 2000; Ives & Carpenter, 2007)(表3)。其中抵抗力用于描述群落免受外界干扰而保持原状的能力; 而恢复力则是描述群落受到外界干扰后回到原来状态的能力。脆弱性和稳健性用于测度生态群落或者生态系统对环境变化的忍受程度。因此, 在环境改变不大的条件下能保持稳定的群落或系统, 称之为脆弱系统; 而在很大的环境改变范围中能保持稳定的系统称之为稳健系统(Thompson et al., 2012)。因此, 相关研究应注意区分不同的相互作用类型以及稳定性的测度。

表3 关于群落(生态系统)稳定性的相关概念

Table 3

| 概念 Concept | 解释 Explanation |

|---|---|

| 复杂性 Complexity | 用于描述群落和网络的复杂程度, 通常用网络的连接度来表征 Describing the extent of complex a community (network), which measured as connectance |

| 抵抗力 Residence | 群落和互作网络免受外界干扰而保持原状的能力 The system return to its ecological regime after a perturbation in the state of the system |

| 恢复力 Resilience | 群落受到外界干扰后回到原来状态的能力 Return time to ecological regime after a perturbation |

| 持久性 Persistence | 物种在动态网络中持续存在的能力 Proportion of coexisting species at dynamic ecological network |

| 次生灭绝 Second extinction | 群落中某些物种的灭绝导致其他物种随之灭绝的情形 Loss of additional species after the extinction of one target species |

| 稳健性 Robustness | 生态群落或种间互作网络对物种的丧失导致次生灭绝的容忍度, 用灭绝曲线下的面积表示 Resistance of a community (network) against additional extinction after species elimination, measured as the area below the extinction curve |

迄今为止, 已有大量研究来描述互惠网络和拮抗网络等种间互作网络的结构, 并发现它们的结构模式会影响互作网络的稳定性(Bascompte & Jordano, 2013)。种子传播网络、传粉网络等互惠网络常具有较高的嵌套结构和模块结构(Donatti et al., 2011; Mello et al., 2011)。研究发现模块结构和嵌套结构都有利于种间互作网络的稳定(Bascompte & Jordano, 2013), 从而维持较高的生物多样性(Bastolla et al., 2009)。在食物网中, 杂食环、节点连接数的异质分布、嵌套结构和模块化等结构模式都倾向于促进群落稳定性和物种共存(Ives & Carpenter, 2007)。研究表明在改变单个物种多度时, 群落或生态系统的多样性能增进其稳定性(Tilman et al., 2001), 食物网中弱相互作用可能是促进系统稳定的关键因素(McCann et al., 1998; Neutel et al., 2002)。尽管如此, 关于网络的结构和稳定性研究仍有较多争议。不同类型的种间互作网络结构的驱动因子可能存在一定的差异, 使得种间互作网络结构和稳定性的关系与相互作用类型相关(图1)。Allesina和Tang (2012)研究发现在捕食网络中弱相互作用和嵌套结构并不一定利于稳定性。Okuyama和Holland (2008)发现在互惠网络中, 使用恢复力作为群落稳定性的指标时, 群落恢复力的增加与物种多样性和物种相互作用数量(连通性)以及网络嵌套性和对称性相互作用强度的增加有关, 并呈现与传统模式相反的正向复杂性和稳定性的关系。Thébault和Fontaine (2010)发现在互惠网络(传粉网络)中, 高度连接和高度嵌套的网络结构促进了稳定性(恢复力); 而在拮抗网络(植食网络)中, 则是高度模块化和低连接网络促进食物网的稳定性。

3.2 干扰对互作网络结构与稳健性的影响

网络的稳定性会受到一系列人为过程的影响, 如物种和种群的灭绝、生物入侵、栖息地丧失以及生态恢复等。因此, 在环境变化的背景下, 生态群落或生态系统的稳健性受到了持续的关注, 并成为当前种间互作网络稳定性实证和理论研究的热点问题(Saavedra et al., 2008; Pocock et al., 2012; Grass et al., 2018)。群落中某些物种的丧失可能会导致其他物种产生级联的次生灭绝。研究种间互作网络的稳健性对预测群落中的物种丧失和灭绝的影响至关重要。Memmott等(2004)对2个传粉网络的稳定性进行模拟分析, 发现优先去除连接最多的传粉者可导致植物物种多样性的线性下降。

网络的拓扑结构、物种性状、行为及多度均可影响互作网络对物种丧失的稳健性。在结构上, 较高的连接度、模块性和嵌套性等结构, 可促进互作网络的动态稳定性或结构稳定性。例如, 连接度增加会使得消费者次生灭绝的风险降低, 从而增加群落稳定性。在行为上, 存在物种重新连接的互作网络, 其对物种丧失的稳健性要高于那些没有发生重新连接的静态网络, 即当网络中某个物种消失时, 幸存的物种之间形成新的相互作用, 会增加网络稳健性(Kaiser-Bunbury et al., 2010)。同样地, 在传统的食物网中, 由于生态位重叠物种的存在, 会使得某些物种消失时, 捕食者和食物之间形成新的营养相互作用, 因此重叠物种的比例与稳健性高度正相关(Staniczenko et al., 2010)。泛化的优势物种通常在觅食行为上有较高的可塑性, 当它们多度发生改变时, 就会转而使用不同的资源(Kondoh, 2003)。通过这种方式, 它们可以利用已灭绝物种的生态位, 从而保持网络的稳定性和生态系统功能(Valdovinos et al., 2016)。此外, 多度最高的物种是网络稳定的关键, 因为它们往往最不容易灭绝, 并且它们会通过直接或间接的相互作用与网络中的其他物种发生紧密联系(Aizen et al., 2012)。相反, 对于更特化的种间相互作用或网络而言, 环境变化所导致的物种灭绝或相互作用消失的风险往往更大(Aizen et al., 2012; Burkle et al., 2013)。Pocock等(2012)在农业生态系统中对多个类型互作网络的综合研究发现, 不同类型网络对植物丧失的稳健性不同, 其中传粉网络最为脆弱, 且不同类型的网络之间的稳健性并无显著的协同变化。因此, 生态恢复对某一个功能群有利, 不一定对其他功能群也有利。

4 结构多样性与生态系统功能维持

在生态群落中, 捕食者与猎物之间的营养关系(植食、捕食和资源利用型竞争), 不仅是生态系统物质循环和能量流动的决定因素, 而且能够通过改变自然选择压力来影响生物群落中物种间的遗传变异程度(Pimm & Pimm, 1982)。营养级内和营养级间的物种对环境变化的差异性通过种间竞争、上行或下行控制的非对称性响应可能导致群落结构的再组织, 进而改变生物多样性格局以及生态系统过程和功能(Chase, 2000)。在种间互作网络中, 既有广受关注的营养关系, 也有复杂的非营养关系。描述和定量网络中不同组分间的相互关系及其作用强度, 不仅可以阐明群落物种多样性的维持机制和生物多样性影响生态系统功能的作用机理, 而且可通过建立网络模型来预测当前全球变化和物种多样性丧失背景下生态系统结构和功能的演变趋势。

4.1 营养关系和非营养关系的生态效应

捕食者-猎物营养关系的生态效应包含捕食者对猎物的消耗效应和非消耗效应等作用机制。关于捕食者对猎物的消耗效应研究最早可追溯到20世纪60年代提出的营养级联效应理论(Hairston et al., 1960)。以捕食者-草食者-植物三级食物链为例, 捕食者通过直接捕食草食动物而降低其数量, 从而减轻了草食动物对植物的压力。因此, 处于食物链不同位置的物种对环境变化的响应并不一致(Liao et al., 2017)。传统的群落生态学观点认为, 能量需经过食物链传递。基于能量守恒定律, 食物网中捕食者-猎物之间最基础、最直接的关系就是消耗型的营养关系。无论是关键捕食者效应、营养级联效应, 还是非对称竞争均可看作是由于食物网内物种的丰富度变化衍生而来的(Paine, 1966; Oksanen et al., 1981)。但是, 如果把物种作为群落生态学的基本组成单元, 那么物种本身固有的特征才是种间关系发生的真正决定因素(Abrams, 1992)。例如, 捕食者捕食猎物时通常由捕食者特征(大小、速度、捕食工具、搜寻能力、追击策略)和猎物特征(如感知能力、大小、速度、形态和隐藏策略)共同影响。在这种情况下, 捕食者不能直接杀死猎物或是捕食者对猎物所产生的捕食压力不足以使猎物强烈地感受到, 但猎物仍会产生在大小、活动、形态和行为等特征上的改变以躲避捕食者, 这就是所谓的非消耗效应。任何猎物在其一生中无时无刻不面临着捕食者的压力, 捕食者对猎物特征的影响涉及猎物整个种群的变化, 是长期和具有遗传性的。这种效果比起猎物仅仅在数量上的变化影响更为深远(Werner & Peacor, 2003)。因此, 非消耗型的营养关系在预测群落动态的理论框架中已越来越重要。

鉴于营养关系的重要性, 在传统的食物网研究中, 往往忽视自然群落中物种间的非营养关系(共生、传粉、种子传播、干扰性竞争、偏害和“工程师”效应)。但这些非营养关系是普遍存在的(Goudard & Loreau, 2008)。例如, 在非洲稀树草原的大象经常连根拔起灌木和乔木的幼树, 甚至成体, 但并不以这些本木植物为食物, 大象和这些植物之间不存在物质和能量转移的营养关系。然而, 大象的这种行为可能减少一些其他动物的食物资源或庇护所, 因此这种行为可能是维持草地群落结构和功能的一种重要机制(Coverdale et al., 2016)。近年来, 人们逐渐认识到非营养关系能够修饰食物网结构及其生态系统功能(Arditi et al., 2005; Goudard & Loreau, 2008; Kéfi et al., 2012)。其中, 碎屑食物网中的非营养关系在碎屑分解过程中的作用可能大于营养关系(Majdi et al., 2014)。模型分析表明, 对于存在着非营养关系如互利共生的群落而言, 非营养关系的作用强度越大, 越有利于高效的生物群落构建(Arditi et al., 2005)。在地上与地下的连接网络中, 碎屑食物网中的捕食者可以通过抑制碎屑分解者, 降低碎屑分解速率, 从而进一步降低土壤养分浓度以及植物生长速率(Wu et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2013)。从碎屑食物网中的捕食者到植物的过程是被碎屑和土壤等非生物组分分离的, 因此整个级联效应的过程既包括营养关系, 也包括非营养关系。将两种关系完整结合起来的研究, 虽然对种间互作网络研究非常重要, 但在当前的群落生态学研究中还很少涉及。

“生态系统工程师”是自然生物群落的一种重要现象, 其功能主要体现在植物或动物物种或种群通过改变周围生物和非生物条件而影响其他生物的生存状况(Sanders et al., 2014)。在这种情况下, “生态系统工程师”与受影响的生物之间的关系也是种间互作网络中的一种重要的非营养关系类型。例如, 蚯蚓通过改变土壤物理结构和化学组成影响其他土壤节肢动物群落结构和植物生长, 但是蚯蚓与土壤节肢动物和植物之间不存在营养关系(Eisenhauer, 2010)。“生态系统工程师”的生境修饰或重建能够增加营养级水平和食物链长度, 从而增加食物网的复杂性和稳定性(Sanders et al., 2014)。

4.2 生态系统功能稳定性

全球变化和人类活动使生物多样性受到了严重的威胁, 而生物多样性的丧失会对生态系统功能产生负面影响(Dirzo et al., 2014)。自20世纪90年代以来, 生物多样性与生态系统功能(Biodiversity and Ecosystem Fucntioning, BEF)研究极大地推动了生态学理论的发展, 而且对预测生物多样性丧失对生态系统功能的影响有潜在的应用价值, 同时对生物多样性保护和探究生态系统功能维持有着重要的指导意义(Tilman et al., 2014)。在传统BEF研究中, 主要集中在针对单一营养级水平进行小规模试验, 通过物种丰富度或功能多样性以及系统发育多样性对生态系统功能的影响将生物多样性与生态系统功能联系起来。然而, 目前对种间互作网络结构和BEF之间的关系仍然缺乏相关研究。因此, 网络结构与生态系统功能维持是种间互作网络研究需要突破的一个重要问题(Bascompte & Jordano, 2013; Schleuning et al., 2015)。

尽管种间互作网络和生态系统功能的关系的研究尚处于初始阶段, 但在概念、理论以及实证等方面也取得了一些成果。首先, 种间互作和网络结构与生态系统功能之间存在线性或非线性的关系。与物种多样性与生态系统功能关系类似, 研究发现在互惠传粉网络中, 较高的蜜蜂多样性会增加种子产量, 但是与蜜蜂多样性相比, 蜜蜂物种间的功能互补性能更好地解释种子产量的变化, 即增加功能生态位(即网络特化水平和模块结构), 更能实现传粉的成功(Fründ et al., 2013)。在种子传播网络中, 鸟类多度和多样性促进种子扩散, 而且被扩散的种子密度随着种子传播网络的特化水平增加而增加, 表明植物-食果鸟互作网络的特化程度驱动了大尺度的种子传播过程(García et al., 2018)。在一定的营养供给条件下, 食物网中的总营养摄入量随食物网的垂直多样性增加而增加(Wang & Brose, 2018)。此外, 在拮抗网络中决定寄生虫共享宿主的因素(即宿主-寄生虫网络的结构)可能会影响种间寄生虫的传播和疾病传播模式(Pilosof et al., 2015)。其次, 生态系统功能稳定性在一定程度上与种间互作网络的稳健性相关, 而物种冗余(或互补)、嵌套结构以及模块结构可影响种间互作网络的稳定性(Memmott et al., 2004), 因此生态系统的稳定性可以通过网络的结构以及结构的稳定性来预测。年际间共享的植物和传粉者, 在网络中处于相对稳定的位置, 且相对泛化物种构成了稳定的传粉网络内核, 这些物种可能与网络结构和生态功能稳定性的维持有关(Fang & Huang, 2012)。此外, 植物物种多样性能影响多个高营养级的相互作用多样性, 而这些相互作用本身就是生态系统功能, 如植食、寄生等。在BEF-China的一系列研究中发现, 植物多样性会促进多个更高营养级的种间相互作用(Staab et al., 2015, 2016; Fornoff et al., 2019), 会改变蚂蚁-半翅目互作多样性与植食率的关系(Schuldt et al., 2017)。然而, 这些研究均未直接分析种间互作网络结构与生态系统功能的关系。Schleuning等(2015)提出了整合功能多样性、互作网络结构和生态系统功能研究的概念框架, 但仍需有关实证研究。

5 问题和展望

综上所述, 种间互作网络的研究在近30年的发展为生态学家全面认识物种共存、群落构建机制、稳定性维持机制、生物多样性和生态系统功能关系提供了新的角度。在今后的研究中, 如何利用机器学习和多层网络等来探究环境变化对种间互作网络结构和功能的影响, 并亟待加强理论和实证的整合性研究。

5.1 网络结构的预测

通过已知的种间互作网络结构可用于预测生态系统功能的动态以及由环境变化所导致的生态后果。然而, 在一个群落中, 种间互作网络数据获取要比生物多样性数据获取的难度大得多。目前, 已有大量的全球共享的生物多样性数据库可供使用, 如分子数据库(如NCBI), 物种系统发育数据库(如Phylomatic、BirdTree等)、功能性状(如TRY)、物种分布数据库(如GBIF)等(王昕等, 2017; 张健, 2017)。关键在于能否利用这些已知的种间互作网络的构建机制, 以及相关生物多样性数据来预测群落中的物种间是否发生相互作用。根据前文所述的种间互作网络的构建机制, 目前已有多个统计模型来推断物种之间相互作用发生的概率以及网络结构特征(如: 传粉网络: Vázquez et al., 2009b; 植食网络: Pearse & Altermatt, 2013; 食物网: Gravel et al., 2013; Gray et al., 2015; Pomeranz et al., 2019)。这些统计模型主要以特征匹配和系统发育关系机制为主。然而, 这些模型对应对当前的生态大数据来说存在一定的局限性。生态大数据往往是高维度的, 变量之间存在着非线性和复杂的交互作用, 同时变量之间存在较多的缺失值(Cutler et al., 2007)。应用传统的统计方法很难克服如过拟合和多重共线性等问题, 不利于对这些数据进行深入分析。因此, 拓展新的模型和算法显得尤其必要。近年来, 随机森林、支持向量机(SVM)、卷积神经网络(CNN)等机器学习模型因其解释简单、分类精度高、能够表征变量间复杂的相互作用而被生态学家广泛应用(Cutler et al., 2007), 但如何来推断物种间的相互作用仍有待研究(Derocles et al., 2018)。总之, 运用生态大数据和有关机器学习算法在分析和推断物种间的相互作用方面有着宽广的发展前景。

5.2 多层互作网络的研究

多层或多维度的互作网络是近年来生态网络研究领域的一个新方向(Pilosof et al., 2017)。尽管多层网络在社会学和物理学领域有着较好的理论和应用基础(Boccaletti et al., 2014), 但是在生态学领域, 有关理论和方法的研究仍有待开展(Hutchinson et al., 2018)。一个多层网络由4个部分构成: 一组表征实体的“物理节点”, 如物种; 一组不同的“层”; 一组“状态节点”, 状态节点指的是物理节点在特定层上的表现; 一组“边”或称之为连接, 把多层网络中的状态节点连接起来, 这些边(连接)像传统的种间互作网络一样可以带权重或不带权重, 分为层内连接和层间连接。层可以通过不同的研究系统来定义: 通过跨空间或时间层定义, 例如不同斑块和不同季节; 通过不同互作类型定义, 例如植食层、传粉层以及种子扩散层等; 通过不同的功能群组来定义以及通过一个组织中不同水平来定义等。生态多层网络更能代表自然界中的真实情况, 因此, 无论是理论生态学还是实验生态学, 都应加强多层网络的研究, 以揭示生态系统过程以及生态系统功能的维持机制。当前生态多层网络研究的难点包括两个方面: 一是如何找到具有生态学和生物学意义的多层网络结构指数, 二是如何测度层与层之间连接的权重。针对第一个方面, 目前已有一些指数用于描述多层网络的结构和功能, 如模块性(Pilosof et al., 2017; Timóteo et al., 2018)、连通性、物种的角色(Hackett et al., 2019)等。但是, 这些结构指数仍不足以描述多层网络的复杂结构和功能, 仍需继续开发新的结构指数和预测指数。针对第二方面, Hutchinson等(2018)提出了一系列方案来测度层与层之间连接的强度(例如物种在斑块间的扩散、多度的差异和不同相互作用类型间的依赖性等), 在目前仅有的几个案例中, 大部分未加权重, 或者把权重设置为从小到无穷大的梯度再进行计算。因此, 这一系列的测度方法仍需大量的实验来检验。此外, 层间连接和层内连接是如何相互影响的也需要加强研究。例如, 在空间的种子传播多层网络中, 动物在斑块间的移动会影响到某个斑块内动物对植物的取食强度, 同样斑块内食物资源的丰富程度以及动植物间互作的强度会影响到动物的移动以及植物在斑块间的传播。而在多种互作类型的多层网络中, 层与层之间的依赖关系会影响到层内的连接, 例如通过传粉层所实现的结实率(与种子传播层的连接)会影响到食果动物和植物的互作强度。

5.3 种间互作网络结构和功能对环境变化的响应

全球生物多样性格局面临来自人类活动干扰和全球气候变化等的威胁: 一方面生态群落中生物多样性呈显著降低的趋势, 大量物种加速灭绝; 另一方面生物多样性变化显著改变了种间互作的格局, 引起食物链的断裂, 可能促使其他物种的相继灭绝, 从而影响生态系统功能和过程(Morris, 2010; Thompson et al., 2012)。全球变化所造成的生物多样性变化(如某个物种或功能群的丧失或灭绝)可显著改变群落内物种间直接作用和间接作用的格局和强度, 导致相互作用的物种或功能群随之消失, 从而改变物种间的互作网络, 对群落结构与功能、多样性与稳定性产生显著影响(Dyer et al., 2010; Tylianakis et al., 2010; Pocock et al., 2012)。因此, 探究种间互作网络结构和生态功能随环境梯度的变化是当前生态学的热点问题之一(Tylianakis & Morris, 2017)。相关研究结果对揭示和预测生物多样性丧失或功能性灭绝所产生的生态后果, 以及对生态系统管理、生物多样性保护和生态恢复等均有重要的实践价值。环境变化对种间互作网络结构和功能的影响可以通过设定一系列自然环境梯度(如纬度梯度、海拔梯度、干扰梯度等)和人工操控梯度(如温度梯度、降水梯度等)来研究。例如, Tylianakis和Morris (2017)对种间互作网络对环境梯度变化的模式、潜在机制以及时空过程对网络的塑造等方面进行了全面的综述; Peters等(2019)利用较为翔实的数据探究了气候因子和土地利用对热带多个营养级的生物多样性和多种生态系统功能的影响。然而, 以往有关种间互作网络、生态系统功能对环境梯度的响应机制大多是独立开展的, 而极少探究种间互作网络结构与生态系统功能的关系如何随环境梯度的变化而变化。此外, 在网络随环境梯度变化的研究中, 都是把各个网络当作一个独立的单元来对待, 从而忽略了网络间的各物种存在物种迁移扩散的事实。因此, 采用上述多层网络模型同时考虑不同维度的生物多样性(尤其是功能多样性)、种间互作网络结构以及生态系统功能, 有助于揭示种间互作和生态系统功能对环境梯度的响应机制。

5.4 加强理论和实证的整合性研究

当前理论研究与实证研究在很大程度上处于相对独立的状态, 导致了目前理论模型预测与实际结果可能存在较多的争论, 因此亟待实验生态学及理论模型研究的有效结合进行相互印证。首先, 理论模型对条件的限制相对严格, 而事实上自然界往往比较复杂, 拓展现有的理论模型更能解释复杂的生态过程和结果。例如将生境损失与破碎化融入当前的食物链模型, 发现处于食物链不同位置的物种对生境丧失与破碎化的响应并不一致(Liao et al., 2016, 2017)。其次, 目前种间互作网络理论模型研究很少同时考虑物种间的直接作用(如捕食、传粉和种子传播等)和间接作用(竞争、促进、似然竞争和似然互惠等), 而这些间接作用在网络的稳定性、物种维持和协同进化扮演着十分重要的角色(Guimarães et al., 2017; Gracia-Lázaro et al., 2018)。同时考虑同一营养级水平的间接作用(水平结构)和营养级间直接作用(垂直结构)及其交互关系对网络结构和功能以及稳定性的影响将成为理论和实证研究的重点内容。第三, 实证研究往往不符合理论模型的限定条件, 导致结果与理论预测相左。故通过一系列人工操纵实验对验证理论模型是十分必要的。此外, 在进行理论模拟分析时, 参数化的过程也十分关键。如这些参数的设置是否符合自然界真实情况对理论模型的预测准确性有着很大的影响, 而这在较大程度上受限于人们对物种自然史和生物学的认知。通常, 分析网络的稳定性时需要对物种的内禀增长率进行参数化, 但目前很多物种内禀增长率的数据依然匮乏。因此, 实现理论研究和实证研究的有效结合有助于预测环境变化对种间互作网络结构和稳定性以及生态系统功能的影响。

参考文献

Predators that benefit prey and prey that harm predators: unusual effects of interacting foraging adaptation

DOI:10.1086/285429 URL [本文引用: 1]

Specialization and rarity predict nonrandom loss of interactions from mutualist networks

DOI:10.1126/science.1215320 URL [本文引用: 2]

Plant and animal functional diversity drive mutualistic network assembly across an elevational gradient

DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-05610-w

PMID:30093613

[本文引用: 1]

Species' functional traits set the blueprint for pair-wise interactions in ecological networks. Yet, it is unknown to what extent the functional diversity of plant and animal communities controls network assembly along environmental gradients in real-world ecosystems. Here we address this question with a unique dataset of mutualistic bird-fruit, bird-flower and insect-flower interaction networks and associated functional traits of 200 plant and 282 animal species sampled along broad climate and land-use gradients on Mt. Kilimanjaro. We show that plant functional diversity is mainly limited by precipitation, while animal functional diversity is primarily limited by temperature. Furthermore, shifts in plant and animal functional diversity along the elevational gradient control the niche breadth and partitioning of the respective other trophic level. These findings reveal that climatic constraints on the functional diversity of either plants or animals determine the relative importance of bottom-up and top-down control in plant-animal interaction networks.

Stability criteria for complex ecosystems

DOI:10.1038/nature10832 URL [本文引用: 1]

Rheagogies: modelling non-trophic effects in food webs

DOI:10.1016/j.ecocom.2005.04.003 URL [本文引用: 2]

Plant-animal mutualistic networks: the architecture of biodiversity

DOI:10.1146/ecolsys.2007.38.issue-1 URL [本文引用: 1]

The nested assembly of plant-animal mutualistic networks

Most studies of plant-animal mutualisms involve a small number of species. There is almost no information on the structural organization of species-rich mutualistic networks despite its potential importance for the maintenance of diversity. Here we analyze 52 mutualistic networks and show that they are highly nested; that is, the more specialist species interact only with proper subsets of those species interacting with the more generalists. This assembly pattern generates highly asymmetrical interactions and organizes the community cohesively around a central core of interactions. Thus, mutualistic networks are neither randomly assembled nor organized in compartments arising from tight, parallel specialization. Furthermore, nestedness increases with the complexity (number of interactions) of the network: for a given number of species, communities with more interactions are significantly more nested. Our results indicate a nonrandom pattern of community organization that may be relevant for our understanding of the organization and persistence of biodiversity.

The architecture of mutualistic networks minimizes competition and increases biodiversity

DOI:10.1038/nature07950 URL [本文引用: 1]

Manifold influences of phylogenetic structure on a plant-herbivore network

DOI:10.1111/oik.2017.v126.i5 URL [本文引用: 1]

What do interaction network metrics tell us about specialization and biological traits

The structure of ecological interaction networks is often interpreted as a product of meaningful ecological and evolutionary mechanisms that shape the degree of specialization in community associations. However, here we show that both unweighted network metrics (connectance, nestedness, and degree distribution) and weighted network metrics (interaction evenness, interaction strength asymmetry) are strongly constrained and biased by the number of observations. Rarely observed species are inevitably regarded as "specialists," irrespective of their actual associations, leading to biased estimates of specialization. Consequently, a skewed distribution of species observation records (such as the lognormal), combined with a relatively low sampling density typical for ecological data, already generates a "nested" and poorly "connected" network with "asymmetric interaction strengths" when interactions are neutral. This is confirmed by null model simulations of bipartite networks, assuming that partners associate randomly in the absence of any specialization and any variation in the correspondence of biological traits between associated species (trait matching). Variation in the skewness of the frequency distribution fundamentally changes the outcome of network metrics. Therefore, interpretation of network metrics in terms of fundamental specialization and trait matching requires an appropriate control for such severe constraints imposed by information deficits. When using an alternative approach that controls for these effects, most natural networks of mutualistic or antagonistic systems show a significantly higher degree of reciprocal specialization (exclusiveness) than expected under neutral conditions. A higher exclusiveness is coherent with a tighter coevolution and suggests a lower ecological redundancy than implied by nested networks.

The structure and dynamics of multilayer networks

DOI:10.1016/j.physrep.2014.07.001 URL [本文引用: 1]

Plant-pollinator interactions over 120 years: loss of species, co-occurrence, and function

DOI:10.1126/science.1232728

PMID:23449999

[本文引用: 1]

Using historic data sets, we quantified the degree to which global change over 120 years disrupted plant-pollinator interactions in a temperate forest understory community in Illinois, USA. We found degradation of interaction network structure and function and extirpation of 50% of bee species. Network changes can be attributed to shifts in forb and bee phenologies resulting in temporal mismatches, nonrandom species extinctions, and loss of spatial co-occurrences between extant species in modified landscapes. Quantity and quality of pollination services have declined through time. The historic network showed flexibility in response to disturbance; however, our data suggest that networks will be less resilient to future changes.

Are there real differences among aquatic and terrestrial food webs

DOI:10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01942-X URL [本文引用: 1]

Elephants in the understory: opposing direct and indirect effects of consumption and ecosystem engineering by megaherbivores

DOI:10.1002/ecy.1557

PMID:27870025

[本文引用: 1]

Positive indirect effects of consumers on their resources can stabilize food webs by preventing overexploitation, but the coupling of trophic and non-trophic interactions remains poorly integrated into our understanding of community dynamics. Elephants engineer African savanna ecosystems by toppling trees and breaking branches, and although their negative effects on trees are well documented, their effects on small-statured plants remain poorly understood. Using data on 117 understory plant taxa collected over 7 yr within 36 1-ha experimental plots in a semi-arid Kenyan savanna, we measured the strength and direction of elephant impacts on understory vegetation. We found that elephants had neutral effects on most (83-89%) species, with a similar frequency of positive and negative responses among the remainder. Overall, estimated understory biomass was 5-14% greater in the presence of elephants across a range of rainfall levels. Whereas direct consumption likely accounts for the negative effects, positive effects are presumably indirect. We hypothesized that elephants create associational refuges for understory plants by damaging tree canopies in ways that physically inhibit feeding by other large herbivores. As predicted, understory biomass and species richness beneath elephant-damaged trees were 55% and 21% greater, respectively, than under undamaged trees. Experimentally simulated elephant damage increased understory biomass by 37% and species richness by 49% after 1 yr. Conversely, experimentally removing elephant damaged branches decreased understory biomass by 39% and richness by 30% relative to sham-manipulated trees. Camera-trap surveys revealed that elephant damage reduced the frequency of herbivory by 71%, whereas we detected no significant effect of damage on temperature, light, or soil moisture. We conclude that elephants locally facilitate understory plants by creating refuges from herbivory, which countervails the direct negative effects of consumption and enhances larger-scale biomass and diversity by promoting the persistence of rare and palatable species. Our results offer a counterpoint to concerns about the deleterious impacts of elephant "overpopulation" that should be considered in debates over wildlife management in African protected areas: understory species comprise the bulk of savanna plant biodiversity, and their responses to elephants are buffered by the interplay of opposing consumptive and non-consumptive interactions.© 2016 by the Ecological Society of America.

Random Forests for classification in ecology

DOI:10.1890/07-0539.1 URL [本文引用: 2]

Historical climate-change influences modularity and nestedness of pollination networks

DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2013.00201.x URL [本文引用: 1]

Biomonitoring for the 21st Century: integrating next- generation sequencing into ecological network analysis

Defaunation in the Anthropocene

DOI:10.1126/science.1251817 URL [本文引用: 1]

Analysis of a hyper-diverse seed dispersal network: modularity and underlying mechanisms

DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01639.x

PMID:21699640

[本文引用: 2]

Mutualistic interactions involving pollination and ant-plant mutualistic networks typically feature tightly linked species grouped in modules. However, such modularity is infrequent in seed dispersal networks, presumably because research on those networks predominantly includes a single taxonomic animal group (e.g. birds). Herein, for the first time, we examine the pattern of interaction in a network that includes multiple taxonomic groups of seed dispersers, and the mechanisms underlying modularity. We found that the network was nested and modular, with five distinguishable modules. Our examination of the mechanisms underlying such modularity showed that plant and animal trait values were associated with specific modules but phylogenetic effect was limited. Thus, the pattern of interaction in this network is only partially explained by shared evolutionary history. We conclude that the observed modularity emerged by a combination of phylogenetic history and trait convergence of phylogenetically unrelated species, shaped by interactions with particular types of dispersal agents.© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd/CNRS.

Identifying causes of patterns in ecological networks: opportunities and limitations

DOI:10.1146/ecolsys.2017.48.issue-1 URL [本文引用: 2]

Introducing the bipartite package: analysing ecological networks

Ecological modules and roles of species in heathland plant-insect flower visitor networks

DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01501.x

PMID:19021779

[本文引用: 1]

1. Co-existing plants and flower-visiting animals often form complex interaction networks. A long-standing question in ecology and evolutionary biology is how to detect nonrandom subsets (compartments, blocks, modules) of strongly interacting species within such networks. Here we use a network analytical approach to (i) detect modularity in pollination networks, (ii) investigate species composition of modules, and (iii) assess the stability of modules across sites. 2. Interactions between entomophilous plants and their flower-visitors were recorded throughout the flowering season at three heathland sites in Denmark, separated by >or= 10 km. Among sites, plant communities were similar, but composition of flower-visiting insect faunas differed. Visitation frequencies of visitor species were recorded as a measure of insect abundance. 3. Qualitative (presence-absence) interaction networks were tested for modularity. Modules were identified, and species classified into topological roles (peripherals, connectors, or hubs) using 'functional cartography by simulated annealing', a method recently developed by Guimerà & Amaral (2005a). 4. All networks were significantly modular. Each module consisted of 1-6 plant species and 18-54 insect species. Interactions aggregated around one or two hub plant species, which were largely identical at the three study sites. 5. Insect species were categorized in taxonomic groups, mostly at the level of orders. When weighted by visitation frequency, each module was dominated by one or few insect groups. This pattern was consistent across sites. 6. Our study adds support to the conclusion that certain plant species and flower-visitor groups are nonrandomly and repeatedly associated. Within a network, these strongly interacting subgroups of species may exert reciprocal selection pressures on each other. Thus, modules may be candidates for the long-sought key units of co-evolution.

Diversity of interactions: a metric for studies of biodiversity

DOI:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2009.00624.x URL [本文引用: 1]

The action of an animal ecosystem engineer: identification of the main mechanisms of earthworm impacts on soil microarthropods

DOI:10.1016/j.pedobi.2010.04.003 URL [本文引用: 1]

The dimensionality of ecological networks

DOI:10.1111/ele.12081

PMID:23438174

[本文引用: 1]

How many dimensions (trait-axes) are required to predict whether two species interact? This unanswered question originated with the idea of ecological niches, and yet bears relevance today for understanding what determines network structure. Here, we analyse a set of 200 ecological networks, including food webs, antagonistic and mutualistic networks, and find that the number of dimensions needed to completely explain all interactions is small ( < 10), with model selection favouring less than five. Using 18 high-quality webs including several species traits, we identify which traits contribute the most to explaining network structure. We show that accounting for a few traits dramatically improves our understanding of the structure of ecological networks. Matching traits for resources and consumers, for example, fruit size and bill gape, are the most successful combinations. These results link ecologically important species attributes to large-scale community structure.© 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd/CNRS.

Relative stability of core groups in pollination networks in a biodiversity hotspot over four years

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0032663 URL [本文引用: 2]

Imagine a world without seed dispersers: a review of threats, consequences and future directions

DOI:10.1016/j.baae.2012.02.006 URL [本文引用: 1]

Tree diversity increases robustness of multi-trophic interactions

DOI:10.1098/rspb.2018.2399 [本文引用: 1]

Abundance and generalisation in mutualistic networks: solving the chicken-and- egg dilemma

DOI:10.1111/ele.12535 URL [本文引用: 2]

Bee diversity effects on pollination depend on functional complementarity and niche shifts

DOI:10.1890/12-1620.1 URL [本文引用: 2]

Sampling bias is a challenge for quantifying specialization and network structure: lessons from a quantitative niche model

DOI:10.1111/oik.2016.v125.i4 URL [本文引用: 2]

Frugivore biodiversity and complementarity in interaction networks enhance landscape-scale seed dispersal function

DOI:10.1111/fec.2018.32.issue-12 URL [本文引用: 1]

Nontrophic interactions, biodiversity, and ecosystem functioning: an interaction web model

DOI:10.1086/523945 URL [本文引用: 2]

The joint influence of competition and mutualism on the biodiversity of mutualistic ecosystems

DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-27498-8

PMID:29915176

[本文引用: 1]

In the past years, there have been many advances-but also many debates- around mutualistic communities, whose structural features appear to facilitate mutually beneficial interactions and increase biodiversity, under some given population dynamics. However, most approaches neglect the structure of inter-species competition by adopting a mean-field perspective that does not deal with competitive interactions properly. Here, we build up a multilayer network that naturally accounts for mutualism and competition and show, through a dynamical population model and numerical simulations, that there is an intricate relation between competition and mutualism. Specifically, the multilayer structure is coupled to a dynamical model in which the intra-guild competitive terms are weighted by the abundance of shared mutualistic relations. We find that mutualism does not have the same consequences on the evolution of specialist and generalist species, and that there is a non-trivial profile of biodiversity in the parameter space of competition and mutualism. Our findings emphasize how the simultaneous consideration of positive and negative interactions derived from the real networks is key to understand the delicate trade-off between topology and biodiversity in ecosystems and call for the need to incorporate more realistic interaction patterns when modeling the structural and dynamical stability of mutualistic systems.

Past and potential future effects of habitat fragmentation on structure and stability of plant-pollinator and host-parasitoid networks

DOI:10.1038/s41559-018-0631-2 [本文引用: 1]

Inferring food web structure from predator-prey body size relationships

DOI:10.1111/2041-210X.12103 URL [本文引用: 1]

Joining the dots: an automated method for constructing food webs from compendia of published interactions

DOI:10.1016/j.fooweb.2015.09.001 URL [本文引用: 1]

Indirect effects drive coevolution in mutualistic networks

DOI:10.1038/nature24273 URL [本文引用: 1]

Visulization and pattern analysis of plant-insect pollinator interaction networks in subalpine meadow in Changbai Mountain

长白山高山草甸植物-传粉昆虫相互作用网络可视化及格局分析

Reshaping our understanding of species’ roles in landscape-scale networks

DOI:10.1111/ele.13292

PMID:31207056

[本文引用: 1]

In network ecology, landscape-scale processes are often overlooked, yet there is increasing evidence that species and interactions spill over between habitats, calling for further study of interhabitat dependencies. Here, we investigate how species connect a mosaic of habitats based on the spatial variation of their mutualistic and antagonistic interactions using two multilayer networks, combining pollination, herbivory and parasitism in the UK and New Zealand. Developing novel methods of network analysis for landscape-scale ecological networks, we discovered that few plant and pollinator species acted as connectors or hubs, both within and among habitats, whereas herbivores and parasitoids typically have more peripheral network roles. Insect species' roles depend on factors other than just the abundance of taxa in the lower trophic level, exemplified by larger Hymenoptera connecting networks of different habitats and insects relying on different resources across different habitats. Our findings provide a broader perspective for landscape-scale management and ecological community conservation.© 2019 John Wiley & Sons Ltd/CNRS.

Community structure, population control, and competition

DOI:10.1086/282146 URL [本文引用: 1]

Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: a consensus of current knowledge

DOI:10.1890/04-0922 URL [本文引用: 1]

Seeing the forest for the trees: putting multilayer networks to work for community ecology

Stability and diversity of ecosystems

DOI:10.1126/science.1133258 URL [本文引用: 2]

Sampling networks of ecological interactions

DOI:10.1111/fec.2016.30.issue-12 URL [本文引用: 2]

Invariant properties in coevolutionary networks of plant-animal interactions

DOI:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00403.x URL [本文引用: 3]

The robustness of pollination networks to the loss of species and interactions: a quantitative approach incorporating pollinator behaviour

More than a meal… integrating non-feeding interactions into food webs

DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01732.x URL [本文引用: 1]

Foraging adaptation and the relationship between food-web complexity and stability

DOI:10.1126/science.1079154 URL [本文引用: 1]

Food webs are built up with nested subwebs

DOI:10.1890/09-2219.1 URL [本文引用: 1]

Diverse responses of species to landscape fragmentation in a simple food chain

DOI:10.1111/jane.2017.86.issue-5 URL [本文引用: 2]

An extended patch-dynamic framework for food chains in fragmented landscapes

DOI:10.1038/srep33100 URL [本文引用: 1]

Fluctuations of animal populations and a measure of community stability

DOI:10.2307/1929601 URL [本文引用: 1]

Morphological traits determine specialization and resource use in plant-hummingbird networks in the neotropics

DOI:10.1890/13-2261.1 URL [本文引用: 1]

Predator effects on a detritus-based food web are primarily mediated by non-trophic interactions

DOI:10.1111/1365-2656.12189 URL [本文引用: 1]

Changes in host-parasitoid food web structure with elevation

DOI:10.1111/1365-2656.12285

PMID:25244661

[本文引用: 1]

Gradients in elevation are increasingly used to investigate how species respond to changes in local climatic conditions. Whilst many studies have shown elevational patterns in species richness and turnover, little is known about how food web structure is affected by elevation. Contrasting responses of predator and prey species to elevation may lead to changes in food web structure. We investigated how the quantitative structure of a herbivore-parasitoid food web changes with elevation in an Australian subtropical rain forest. On four occasions, spread over 1 year, we hand-collected leaf miners at twelve sites, along three elevational gradients (between 493 m and 1159 m a.s.l). A total of 5030 insects, including 603 parasitoids, were reared, and summary food webs were created for each site. We also carried out a replicated manipulative experiment by translocating an abundant leaf-mining weevil Platynotocis sp., which largely escaped parasitism at high elevations (≥ 900 m a.s.l.), to lower, warmer elevations, to test if it would experience higher parasitism pressure. We found strong evidence that the environmental change that occurs with increasing elevation affects food web structure. Quantitative measures of generality, vulnerability and interaction evenness decreased significantly with increasing elevation (and decreasing temperature), whilst elevation did not have a significant effect on connectance. Mined plant composition also had a significant effect on generality and vulnerability, but not on interaction evenness. Several relatively abundant species of leaf miner appeared to escape parasitism at higher elevations, but contrary to our prediction, Platynotocis sp. did not experience greater levels of parasitism when translocated to lower elevations. Our study indicates that leaf-mining herbivores and their parasitoids respond differently to environmental conditions imposed by elevation, thus producing structural changes in their food webs. Increasing temperatures and changes in vegetation communities that are likely to result from climate change may have a restructuring effect on host-parasitoid food webs. Our translocation experiment, however, indicated that leaf miners currently escaping parasitism at high elevations may not automatically experience higher parasitism under warmer conditions and future changes in food web structure may depend on the ability of parasitoids to adapt to novel hosts.© 2014 The Authors. Journal of Animal Ecology © 2014 British Ecological Society.

Will a large complex system be stable

DOI:10.1038/238413a0 URL [本文引用: 2]

The diversity-stability debate

DOI:10.1038/35012234 URL [本文引用: 2]

Weak trophic interactions and the balance of nature

DOI:10.1038/27427 URL [本文引用: 1]

The missing part of seed dispersal networks: Structure and robustness of bat-fruit interactions

DOI:10.1371/journal. pone.0017395 URL [本文引用: 1]

Tolerance of pollination networks to species extinctions

Tropical forest loss and its multitrophic effects on insect herbivory

DOI:10.1002/ecy.1592

PMID:27911998

[本文引用: 1]

Forest loss threatens biodiversity, but its potential effects on multitrophic ecological interactions are poorly understood. Insect herbivory depends on complex bottom-up (e.g., resource availability and plant antiherbivore defenses) and top-down forces (e.g., abundance of predators and herbivorous), but its determinants in human-altered tropical landscapes are largely unknown. Using structural equation models, we assessed the direct and indirect effects of forest loss on insect herbivory in 40 landscapes (115 ha each) from two regions with contrasting land-use change trajectories in the Brazilian Atlantic rainforest. We considered landscape forest cover as an exogenous predictor and (1) forest structure, (2) abundance of predators (birds and arthropods), and (3) abundance of herbivorous arthropods as endogenous predictors of insect leaf damage. From 12 predicted pathways, 11 were significant and showed that (1) leaf damage increases with forest loss (direct effect); (2) leaf damage increases with forest loss through the simplification of vegetation structure and its associated dominance of herbivorous insects (indirect effect); and further demonstrate (3) a lack of top-down control of herbivores by predators (birds and arthropods). We conclude that forest loss favors insect herbivory by undermining the bottom-up control (presumably reduced plant antiherbivore defense mechanisms) in forests dominated by fast-growing pioneer plant species, and by improving the conditions required for herbivores proliferation.© 2016 by the Ecological Society of America.

Anthropogenic impacts on tropical forest biodiversity: a network structure and ecosystem functioning perspective

DOI:10.1098/rstb.2010.0273 URL [本文引用: 1]

Stability in real food webs: weak links in long loops

DOI:10.1126/science.1068326 URL [本文引用: 1]

Exploitation ecosystems in gradients of primary productivity

DOI:10.1086/283817 URL [本文引用: 1]

Network structural properties mediate the stability of mutualistic communities

DOI:10.1111/ele.2008.11.issue-3 URL [本文引用: 1]

Missing and forbidden links in mutualistic networks

DOI:10.1098/rspb.2010.1371 URL [本文引用: 1]

The modularity of pollination networks

In natural communities, species and their interactions are often organized as nonrandom networks, showing distinct and repeated complex patterns. A prevalent, but poorly explored pattern is ecological modularity, with weakly interlinked subsets of species (modules), which, however, internally consist of strongly connected species. The importance of modularity has been discussed for a long time, but no consensus on its prevalence in ecological networks has yet been reached. Progress is hampered by inadequate methods and a lack of large datasets. We analyzed 51 pollination networks including almost 10,000 species and 20,000 links and tested for modularity by using a recently developed simulated annealing algorithm. All networks with >150 plant and pollinator species were modular, whereas networks with <50 species were never modular. Both module number and size increased with species number. Each module includes one or a few species groups with convergent trait sets that may be considered as coevolutionary units. Species played different roles with respect to modularity. However, only 15% of all species were structurally important to their network. They were either hubs (i.e., highly linked species within their own module), connectors linking different modules, or both. If these key species go extinct, modules and networks may break apart and initiate cascades of extinction. Thus, species serving as hubs and connectors should receive high conservation priorities.

Food web complexity and species diversity

DOI:10.1086/282400 URL [本文引用: 1]

Predicting novel trophic interactions in a non-native world

DOI:10.1111/ele.12143

PMID:23800217

[本文引用: 1]

Humans are altering the global distributional ranges of plants, while their co-evolved herbivores are frequently left behind. Native herbivores often colonise non-native plants, potentially reducing invasion success or causing economic loss to introduced agricultural crops. We developed a predictive model to forecast novel interactions and verified it with a data set containing hundreds of observed novel plant-insect interactions. Using a food network of 900 native European butterfly and moth species and 1944 native plants, we built an herbivore host-use model. By extrapolating host use from the native herbivore-plant food network, we accurately forecasted the observed novel use of 459 non-native plant species by native herbivores. Patterns that governed herbivore host breadth on co-evolved native plants were equally important in determining non-native hosts. Our results make the forecasting of novel herbivore communities feasible in order to better understand the fate and impact of introduced plants. © 2013 John Wiley & Sons Ltd/CNRS.

Merging evolutionary history into species interaction networks

DOI:10.1111/fec.2016.30.issue-12 URL [本文引用: 1]

Climate-land-use interactions shape tropical mountain biodiversity and ecosystem functions

DOI:10.1038/s41586-019-1048-z URL [本文引用: 1]

Potential parasite transmission in multi-host networks based on parasite sharing

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0117909 URL [本文引用: 1]

The multilayer nature of ecological networks

DOI:10.1038/s41559-017-0101 [本文引用: 2]

Resource use, competition, and resource availability in Hawaiian honeycreepers

DOI:10.2307/1938873 URL [本文引用: 1]

The robustness and restoration of a network of ecological networks

DOI:10.1126/science.1214915 URL [本文引用: 3]

Inferring predator-prey interactions in food webs

DOI:10.1111/2041-210X.13125

[本文引用: 1]

Food webs are a powerful way to represent the diversity, structure, and function of ecological systems. However, the accurate description of food webs requires significant effort in time and resources, limiting their widespread use in ecological studies. Newly published methods allow for the inference of feeding interactions using proxy variables. Here, we compare the accuracy of two recently described methods, as well as describe a composite model of the two, for the inference of feeding interactions using a large, well-described dataset. Both niche and neutral processes are involved in determining whether or not two species will form a feeding link in communities. Three different models for determining niche constraints of feeding interactions are compared, and all three models are extended by incorporating neutral processes, based on relative abundances. The three models compared here infer niche processes through (a) phylogenetic relationships, (b) local species trait distributions (e.g., body size), and (c) a composite of phylogeny and local traits. We show that all three methods perform well at predicting individual species interactions, and that these individual predictions scale up to the network level, resulting in food web structure of inferred networks being similar to their empirical counterparts. Our results indicate that inferring food web structure using phylogenies can be an efficient way of getting summary webs with minimal data, and offers a conservative test of changes in food web structure, particularly when there is low species turnover between sites. Inferences made using traits require more data, but allows for greater understanding of the mechanisms underlying trophic interactions. A composite model of the two methods provides a framework for investigating the importance of how phylogeny, trait distributions, and relative abundances, affect species interactions, and network structure.

Phylogeny determines the role of helminth parasites in intertidal food webs

DOI:10.1111/1365-2656.12101 URL [本文引用: 1]

Compartments in a marine food web associated with phylogeny, body mass, and habitat structure

DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01327.x

PMID:19490028

[本文引用: 2]

A long-standing question in community ecology is whether food webs are organized in compartments, where species within the same compartment interact frequently among themselves, but show fewer interactions with species from other compartments. Finding evidence for this community organization is important since compartmentalization may strongly affect food web robustness to perturbation. However, few studies have found unequivocal evidence of compartments, and none has quantified the suite of mechanisms generating such a structure. Here, we combine computational tools from the physics of complex networks with phylogenetic statistical methods to show that a large marine food web is organized in compartments, and that body size, phylogeny, and spatial structure are jointly associated with such a compartmentalized structure. Sharks account for the majority of predatory interactions within their compartments. Phylogenetically closely related shark species tend to occupy different compartments and have divergent trophic levels, suggesting that competition may play an important role structuring some of these compartments. Current overfishing of sharks has the potential to change the structural properties, which might eventually affect the stability of the food web.

Effects of phenotypic complementarity and phylogeny on the nested structure of mutualistic networks

DOI:10.1111/oik.2007.116.issue-11 URL [本文引用: 2]

Asymmetric disassembly and robustness in declining networks

DOI:10.1073/pnas.0804740105

PMID:18936489

[本文引用: 1]

Mechanisms that enable declining networks to avert structural collapse and performance degradation are not well understood. This knowledge gap reflects a shortage of data on declining networks and an emphasis on models of network growth. Analyzing >700,000 transactions between firms in the New York garment industry over 19 years, we tracked this network's decline and measured how its topology and global performance evolved. We find that favoring asymmetric (disassortative) links is key to preserving the topology and functionality of the declining network. Based on our findings, we tested a model of network decline that combines an asymmetric disassembly process for contraction with a preferential attachment process for regrowth. Our simulation results indicate that the model can explain robustness under decline even if the total population of nodes contracts by more than an order of magnitude, in line with our observations for the empirical network. These findings suggest that disassembly mechanisms are not simply assembly mechanisms in reverse and that our model is relevant to understanding the process of decline and collapse in a broad range of biological, technological, and financial networks.

Integrating ecosystem engineering and food webs

DOI:10.1111/more.2014.123.issue-5 URL [本文引用: 2]

Habitat and fig characteristics influence the bird assemblage and network properties of fig trees from Xishuangbanna, South-West China

DOI:10.1017/S0266467409005847 URL [本文引用: 1]

Beyond neutral and forbidden links: morphological matches and the assembly of mutualistic hawkmoth-plant networks

DOI:10.1111/1365-2656.12509

PMID:26931495

[本文引用: 1]

A major challenge in evolutionary ecology is to understand how co-evolutionary processes shape patterns of interactions between species at community level. Pollination of flowers with long corolla tubes by long-tongued hawkmoths has been invoked as a showcase model of co-evolution. Recently, optimal foraging models have predicted that there might be a close association between mouthparts' length and the corolla depth of the visited flowers, thus favouring trait convergence and specialization at community level. Here, we assessed whether hawkmoths more frequently pollinate plants with floral tube lengths similar to their proboscis lengths (morphological match hypothesis) against abundance-based processes (neutral hypothesis) and ecological trait mismatches constraints (forbidden links hypothesis), and how these processes structure hawkmoth-plant mutualistic networks from five communities in four biogeographical regions of South America. We found convergence in morphological traits across the five communities and that the distribution of morphological differences between hawkmoths and plants is consistent with expectations under the morphological match hypothesis in three of the five communities. In the two remaining communities, which are ecotones between two distinct biogeographical areas, interactions are better predicted by the neutral hypothesis. Our findings are consistent with the idea that diffuse co-evolution drives the evolution of extremely long proboscises and flower tubes, and highlight the importance of morphological traits, beyond the forbidden links hypothesis, in structuring interactions between mutualistic partners, revealing that the role of niche-based processes can be much more complex than previously known.© 2016 The Authors. Journal of Animal Ecology © 2016 British Ecological Society.

Specialization and interaction strength in a tropical plant-frugivore network differ among forest strata

The degree of interdependence and potential for shared coevolutionary history of frugivorous animals and fleshy-fruited plants are contentious topics. Recently, network analyses revealed that mutualistic relationships between fleshy-fruited plants and frugivores are mostly built upon generalized associations. However, little is known about the determinants of network structure, especially from tropical forests where plants' dependence on animal seed dispersal is particularly high. Here, we present an in-depth analysis of specialization and interaction strength in a plant-frugivore network from a Kenyan rain forest. We recorded fruit removal from 33 plant species in different forest strata (canopy, midstory, understory) and habitats (primary and secondary forest) with a standardized sampling design (3447 interactions in 924 observation hours). We classified the 88 frugivore species into guilds according to dietary specialization (14 obligate, 28 partial, 46 opportunistic frugivores) and forest dependence (50 forest species, 38 visitors). Overall, complementary specialization was similar to that in other plant-frugivore networks. However, the plant-frugivore interactions in the canopy stratum were less specialized than in the mid- and understory, whereas primary and secondary forest did not differ. Plant specialization on frugivores decreased with plant height, and obligate and partial frugivores were less specialized than opportunistic frugivores. The overall impact of a frugivore increased with the number of visits and the specialization on specific plants. Moreover, interaction strength of frugivores differed among forest strata. Obligate frugivores foraged in the canopy where fruit resources were abundant, whereas partial and opportunistic frugivores were more common on mid- and understory plants, respectively. We conclude that the vertical stratification of the frugivore community into obligate and opportunistic feeding guilds structures this plant-frugivore network. The canopy stratum comprises stronger links and generalized associations, whereas the lower strata are composed of weaker links and more specialized interactions. Our results suggest that seed-dispersal relationships of plants in lower forest strata are more prone to disruption than those of canopy trees.

Predicting ecosystem functions from biodiversity and mutualistic networks: an extension of trait-based concepts to plant-animal interactions

DOI:10.1111/ecog.2015.v38.i4 URL [本文引用: 3]

Ecological, historical and evolutionary determinants of modularity in weighted seed-dispersal networks

DOI:10.1111/ele.12245

PMID:24467289

[本文引用: 1]

Modularity is a recurrent and important property of bipartite ecological networks. Although well-resolved ecological networks describe interaction frequencies between species pairs, modularity of bipartite networks has been analysed only on the basis of binary presence-absence data. We employ a new algorithm to detect modularity in weighted bipartite networks in a global analysis of avian seed-dispersal networks. We define roles of species, such as connector values, for weighted and binary networks and associate them with avian species traits and phylogeny. The weighted, but not binary, analysis identified a positive relationship between climatic seasonality and modularity, whereas past climate stability and phylogenetic signal were only weakly related to modularity. Connector values were associated with foraging behaviour and were phylogenetically conserved. The weighted modularity analysis demonstrates the dominating impact of ecological factors on the structure of seed-dispersal networks, but also underscores the relevance of evolutionary history in shaping species roles in ecological communities. © 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd/CNRS.

Tree species richness attenuates the positive relationship between mutualistic ant-hemipteran interactions and leaf chewer herbivory

DOI:10.1098/rspb.2017.1489 [本文引用: 1]

Tree diversity alters the structure of a tri-trophic network in a biodiversity experiment

DOI:10.1111/oik.2015.v124.i7 URL [本文引用: 1]

Tree phylogenetic diversity promotes host-parasitoid interactions

DOI:10.1098/rspb.2016.0275 [本文引用: 1]

Size-specific interaction patterns and size matching in a plant-pollinator interaction web.

DOI:10.1093/aob/mcp027 URL [本文引用: 1]

Structural dynamics and robustness of food webs

DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01485.x

PMID:20482578

[本文引用: 1]

Food web structure plays an important role when determining robustness to cascading secondary extinctions. However, existing food web models do not take into account likely changes in trophic interactions ('rewiring') following species loss. We investigated structural dynamics in 12 empirically documented food webs by simulating primary species loss using three realistic removal criteria, and measured robustness in terms of subsequent secondary extinctions. In our model, novel trophic interactions can be established between predators and food items not previously consumed following the loss of competing predator species. By considering the increase in robustness conferred through rewiring, we identify a new category of species--overlap species--which promote robustness as shown by comparing simulations incorporating structural dynamics to those with static topologies. The fraction of overlap species in a food web is highly correlated with this increase in robustness; whereas species richness and connectance are uncorrelated with increased robustness. Our findings underline the importance of compensatory mechanisms that may buffer ecosystems against environmental change, and highlight the likely role of particular species that are expected to facilitate this buffering.

Compartmentalization increases food-web persistence

Stability of ecological communities and the architecture of mutualistic and trophic networks

DOI:10.1126/science.1188321

PMID:20705861

[本文引用: 2]

Research on the relationship between the architecture of ecological networks and community stability has mainly focused on one type of interaction at a time, making difficult any comparison between different network types. We used a theoretical approach to show that the network architecture favoring stability fundamentally differs between trophic and mutualistic networks. A highly connected and nested architecture promotes community stability in mutualistic networks, whereas the stability of trophic networks is enhanced in compartmented and weakly connected architectures. These theoretical predictions are supported by a meta-analysis on the architecture of a large series of real pollination (mutualistic) and herbivory (trophic) networks. We conclude that strong variations in the stability of architectural patterns constrain ecological networks toward different architectures, depending on the type of interaction.

Food webs: reconciling the structure and function of biodiversity

Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning

DOI:10.1146/ecolsys.2014.45.issue-1 URL [本文引用: 1]

Diversity and productivity in a long-term grassland experiment

Plant diversity and niche complementarity had progressively stronger effects on ecosystem functioning during a 7-year experiment, with 16-species plots attaining 2.7 times greater biomass than monocultures. Diversity effects were neither transients nor explained solely by a few productive or unviable species. Rather, many higher-diversity plots outperformed the best monoculture. These results help resolve debate over biodiversity and ecosystem functioning, show effects at higher than expected diversity levels, and demonstrate, for these ecosystems, that even the best-chosen monocultures cannot achieve greater productivity or carbon stores than higher-diversity sites.

Multilayer networks reveal the spatial structure of seed-dispersal interactions across the Great Rift landscapes

DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-02658-y

PMID:29321529

[本文引用: 1]

Species interaction networks are traditionally explored as discrete entities with well-defined spatial borders, an oversimplification likely impairing their applicability. Using a multilayer network approach, explicitly accounting for inter-habitat connectivity, we investigate the spatial structure of seed-dispersal networks across the Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique. We show that the overall seed-dispersal network is composed by spatially explicit communities of dispersers spanning across habitats, functionally linking the landscape mosaic. Inter-habitat connectivity determines spatial structure, which cannot be accurately described with standard monolayer approaches either splitting or merging habitats. Multilayer modularity cannot be predicted by null models randomizing either interactions within each habitat or those linking habitats; however, as habitat connectivity increases, random processes become more important for overall structure. The importance of dispersers for the overall network structure is captured by multilayer versatility but not by standard metrics. Highly versatile species disperse many plant species across multiple habitats, being critical to landscape functional cohesion.

Conservation of species interaction networks

DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2009.12.004 URL [本文引用: 1]

Ecological networks across environmental gradients

DOI:10.1146/ecolsys.2017.48.issue-1 URL [本文引用: 2]

Niche partitioning due to adaptive foraging reverses effects of nestedness and connectance on pollination network stability

DOI:10.1111/ele.12664

PMID:27600659

[本文引用: 1]

Much research debates whether properties of ecological networks such as nestedness and connectance stabilise biological communities while ignoring key behavioural aspects of organisms within these networks. Here, we computationally assess how adaptive foraging (AF) behaviour interacts with network architecture to determine the stability of plant-pollinator networks. We find that AF reverses negative effects of nestedness and positive effects of connectance on the stability of the networks by partitioning the niches among species within guilds. This behaviour enables generalist pollinators to preferentially forage on the most specialised of their plant partners which increases the pollination services to specialist plants and cedes the resources of generalist plants to specialist pollinators. We corroborate these behavioural preferences with intensive field observations of bee foraging. Our results show that incorporating key organismal behaviours with well-known biological mechanisms such as consumer-resource interactions into the analysis of ecological networks may greatly improve our understanding of complex ecosystems.© 2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd/CNRS.

Uniting pattern and process in plant-animal mutualistic networks: a review

DOI:10.1093/aob/mcp057 URL [本文引用: 2]

Evaluating multiple determinants of the structure of plant-animal mutualistic networks

DOI:10.1890/08-1837.1 URL [本文引用: 4]

Processes entangling interactions in communities: forbidden links are more important than abundance in a hummingbird-plant network

DOI:10.1098/rspb. 2013.2397 [本文引用: 2]

Phylogenetic composition of host plant communities drives plant-herbivore food web structure

DOI:10.1111/jane.2017.86.issue-3 URL [本文引用: 1]

Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in food webs: the vertical diversity hypothesis

DOI:10.1111/ele.2018.21.issue-1 URL [本文引用: 1]

Biodiversity information resources. I. Species distribution, catalogue, phylogeny, and life history traits

DOI:10.17520/biods.2017184

[本文引用: 1]

Species distribution, catalogues, phylogeny, and life history traits are the data basis of biodiversity studies, playing critical roles in understanding species origins, evolution, and conservation biodiversity. Recently, a large number of scientific data-sharing platforms have been created, greatly contributing to the development of biodiversity informatics. However, it is difficult for most researchers to deal with big data with high complexity and heterogeneity. Determining how to select and utilize these data accurately and effectively becomes a huge challenge for ecologists and conservation biologists. To better deal with existing problems related to scattered distributed data, we classify biodiversity data resources into four groups (species distribution, catalogues, phylogeny and life history traits), and select representative databases (e.g. Global Biodiversity Information Facility, The Plant List, Open Tree of Life, and The Plant Trait Database (TRY) for demonstration. For each database, data type, and sampling design, geographic coverage and data availability are reported, and selected publications using these datasets are briefly introduced. Meanwhile, we describe recent achievements on the construction of China’s biodiversity digital platforms in each section. Overall, we hope that this paper provides a starting point for researchers to be familiar with these databases and use them correctly, and could have the potential to stimulate the development of related fields in research and conservation of biodiversity under the efforts of researchers and the public.

生物多样性信息资源. I. 物种分布、编目、系统发育与生活史性状

A review of trait-mediated indirect interactions in ecological communities

DOI:10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[1083:AROTII]2.0.CO;2 URL [本文引用: 1]

A brown-world cascade in the dung decomposer food web of an alpine meadow: effects of predator interactions and warming

DOI:10.1890/10-0808.1 URL [本文引用: 1]

Ecological succession drives the structural change of seed-rodent interaction networks in fragmented forests

Biodiversity science and macroecology in the era of big data

DOI:10.17520/biods.2017037

[本文引用: 1]

High-quality biodiversity data are the scientific basis for understanding the origin and maintenance of biodiversity and dealing with its extinction risk. Currently, we identify at least seven knowledge shortfalls or gaps in biodiversity science, including the lack of knowledge on species descriptions, species geographic distributions, species abundance and population dynamics, evolutional history, functional traits, interactions between species and the abiotic environment, and biotic interactions. The arrival of the current era of big data offers a potential solution to address these shortfalls. Big data mining and its applications have recently become the frontier of biodiversity science and macroecology. It is a challenge for ecologists to utilize and effectively analyze the ever-growing quantity of biodiversity data. In this paper, I review several biodiversity-related studies over global, continental, and regional scales, and demonstrate how big data approaches are used to address biodiversity questions. These examples include forest cover changes, conservation ecology, biodiversity and ecosystem functioning, and the effect of climate change on biodiversity. Furthermore, I summarize the current challenges facing biodiversity data collection, data processing and data analysis, and discuss potential applications of big data approaches in the fields of biodiversity science and macroecology.

大数据时代的生物多样性科学与宏生态学

DOI:10.17520/biods.2017037

[本文引用: 1]

高质量的生物多样性数据是认知生物多样性的起源和维持机制及应对其丧失风险的科学基础。当前, 在新物种发现、已知物种的地理分布、种群数量与时空动态、物种进化史、功能性状、物种与环境之间以及物种与物种之间的相互作用等7个方面都存在着知识上的空缺。大数据时代的到来为弥补这些知识空缺提供了可能,大数据的挖掘及其应用最近已成为国际生物多样性与宏生态学研究的前沿内容。如何有效地利用和分析不断增长的生物多样性大数据是生物多样性研究面临的一个极大挑战。本文通过全球、大陆和区域尺度上的研究案例展示了大数据在生物多样性研究中应用的新进展, 内容涉及森林覆盖变化、保护生态学、生物多样性与生态系统功能、气候变化对生物多样性的影响等。最后, 对大数据在生物多样性研究中存在的数据采集、处理和分析等方面的问题进行了总结, 并对其潜在应用前景进行了探讨。

Plant sex affects the structure of plant-pollinator networks in a subtropical forest

DOI:10.1007/s00442-017-3942-0 URL [本文引用: 1]

Predatory beetles facilitate plant growth by driving earthworms to lower-soil layers

DOI:10.1111/jane.2013.82.issue-4 URL [本文引用: 1]

The topological differences between visitation and pollen transport networks: a comparison in species rich communities of the Himalaya-Hengduan Mountains

DOI:10.1111/oik.2019.v128.i4 URL [本文引用: 1]

Floral traits influence pollen vectors’ choices in higher elevation communities in the Himalaya-Hengduan Mountains

DOI:10.1186/s12898-016-0080-1 URL [本文引用: 2]