New compounds from Hydnophytum formicarum young tubers

1

2017

... 在与蚂蚁共生的过程中, 蚁栖植物展现了极具创意性的演化方式.旧热带区茜草科的Myrmecodia与Hydnophytum植物通常生活在低海拔沿海养分贫瘠的环境(Kapitany, 2008).随植株的生长, 其下胚层逐渐扩大并发育出一系列复杂的内腔以营建适宜蚂蚁居住的环境(Volp & Lach, 2019), 内腔通道两旁排列着许多突起的内部根, 能够吸收水和溶解其中的营养物质(Rowe, 2012).蚂蚁入住后在通道内留下多种形式的有机碎屑, 碎屑中的养分最终被内部根吸收供给植物(Abdullah et al., 2017).夹竹桃科眼树莲属(Dischidia)植物通过特化部分叶片, 使其膨大中空, 形成囊状的蚂蚁叶(ant-leaves), 且腔壁上有气孔, 形成一个稳定可控的内部环境(Kapitany, 2008).随着蚂蚁的定居, 特化叶不断收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑, 同时产生不定根从基部开口处向叶内生长蔓延.通过稳定同位素分析表明, 宿主植物叶片中39%的碳来自蚂蚁相关的呼吸作用, 29%的氮来自沉积到蚂蚁叶中的有机碎屑(Treseder et al., 1995).水龙骨科Lecanopteris属植物拥有二型根状茎, 分为有叶着生的实心部分和无叶的空心部分, 空心部分为蚂蚁提供住所(Gay, 1991).使用15N同位素标记的饲养实验证明了蚂蚁活动产生的营养物质可以被Lecanopteris属植物吸收利用(Gay, 1991).鹿角蕨属(Platycerium)的P. ridleyi通过营养叶包裹隆起形成中空区域, 以适宜蚂蚁居住(Franken & Roos, 1982). ...

Micro-site conditions of epiphytic orchids in a human impact gradient in Kathmandu valley, Nepal

1

2012

... 当前研究表明, 在人工环境中保留老树、种植当地树种作为景观树种等措施都有利于附生植物种群的存活(Adhikari et al., 2012).对景观生态学家来说, 如何通过科学合理的规划让原始森林斑块之间保留生态廊道或生态踏脚石, 使附生植物可以在破碎生境中进行基因交流将会是一个很有意义的科学问题. ...

Habitat fragmentation reduces plant progeny quality: a global synthesis

1

2019

... 在社会经济发展的趋势之下, 人类不可避免地需要将更多土地资源用于农业等方面的开发, 导致原始森林被逐渐吞噬.而附生植物高度依赖连续完整且冠层发育良好的原始森林提供生存场所, 土地利用方式的改变成为附生植物最严重的威胁(Flores- Palacios & García-Franco, 2008).目前, 以兰科为代表的很多附生植物都面临着生境丧失或是生境破碎化的风险(李大程等, 2022), 与连续生境相比, 破碎化生境中繁殖的植物后代表现出整体性的遗传冲刷, 削弱了它们应对环境变化的能力, 从而增加了灭绝的风险(Aguilar et al., 2019), 同时传粉者丧失进一步加剧了近亲繁殖和遗传漂变的危害. ...

The associated beetle fauna of Hohenbergia augusta and Vriesea friburgensis (Bromeliaceae) in southern Brazil

3

2016

... Bromeliads plants with tank structure and animals living inside

Table 2 亚科

Subfamily | 属

Genus | 分布

Distribution | 主要共存动物(纲)

Main coexisting fauna (class) | 参考文献

Reference |

沙漠凤梨亚科

Pitcairnioideae | Brocchinia | 南美洲 South America | P | Givnish et al.,1984 |

凤梨亚科

Bromelioideae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A-N, P-T | Freire et al., 2021 |

| Androlepis | 中美洲 Central America | F | Fragoso & Rojas-Fernández, 1996 |

| Araeococcus | 中美洲 Central America | P | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| 水塔花属 Billbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

| Canistrum | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Hohenbergia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Lymania | 中美洲 Central America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Neoregelia | 中美洲 Central America | A, I, M, P, Q, R | Almeida & Souza, 2020 |

| Ronnbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Nidularium | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

... .,

2016 | Lymania | 中美洲 Central America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Neoregelia | 中美洲 Central America | A, I, M, P, Q, R | Almeida & Souza, 2020 |

| Ronnbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Nidularium | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

... .,

2016 | Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

Nematode trophic structure in the phytotelma of Neoregelia cruenta (Bromeliaceae) in relation to microenvironmental and climate variables

1

2020

... Bromeliads plants with tank structure and animals living inside

Table 2 亚科

Subfamily | 属

Genus | 分布

Distribution | 主要共存动物(纲)

Main coexisting fauna (class) | 参考文献

Reference |

沙漠凤梨亚科

Pitcairnioideae | Brocchinia | 南美洲 South America | P | Givnish et al.,1984 |

凤梨亚科

Bromelioideae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A-N, P-T | Freire et al., 2021 |

| Androlepis | 中美洲 Central America | F | Fragoso & Rojas-Fernández, 1996 |

| Araeococcus | 中美洲 Central America | P | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| 水塔花属 Billbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

| Canistrum | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Hohenbergia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Lymania | 中美洲 Central America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Neoregelia | 中美洲 Central America | A, I, M, P, Q, R | Almeida & Souza, 2020 |

| Ronnbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Nidularium | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

Ancient associations of aquatic beetles and tank bromeliads in the Neotropical forest canopy

1

2008

... 分子系统发育研究表明, 一类专性生活在水箱凤梨内的龙虱科昆虫, 其分支起源可追溯至1 200万- 2 300万年前, 这恰好与凤梨科植物在约2 000万年前演化出蓄水叶结构的时间相近(Balke et al., 2008), 以此佐证了水箱凤梨作为一种古老的生境营建者, 在较长的演化时间内都支持着专门的动物群. ...

The canopy starts at 0.5 m: predatory mites (Acari: Mesostigmata) differ between rain forest floor soil and suspended soil at any height

1

2010

... 篮式植物在林冠中重建了一个类似地表的高位土环境(Ortega-Solis et al., 2021), 在满足自身养分与水分需求的同时, 为林冠多种生物营建了理想的生境(Beaulieu et al., 2010).许多动物的生长、繁殖都会依赖篮式植物营建的生境(Phillips et al., 2020), 已记录有15纲97科的动物居住于各类篮式植物中, 其中有90科都是无脊椎动物.以鸟巢蕨为例, 加里曼丹岛热带森林中, 林冠中几乎一半的无脊椎动物生物量汇聚于鸟巢蕨中(Ellwood & Foster, 2004), 在日本南部亚热带森林的研究表明, 鸟巢蕨提升了当地无脊椎动物丰度, 并可以为特定物种提供生境, 有助于在亚热带森林尺度上保持无脊椎动物的高物种多样性(Karasawa & Hijii, 2006).除无脊椎动物之外, 鸟巢蕨是蛙类在林冠中重要的生境, 在吕宋岛南部有近1/5的鸟巢蕨被蛙类利用, 尤其是在白天高温之下, 鸟巢蕨的温、湿度的缓冲能力为蛙类创造了理想的避暑空间, 同时潮湿凉爽的内部环境也是蛙类重要的繁殖场所(Scheffers et al., 2014b).在加里曼丹岛人工安置的32株鸟巢蕨中, 半年后均记录到爬行纲的半叶趾虎(Hemiphyllodactylus typus)及Lipinia vittigera在其中栖息并产卵(Donald et al, 2017b).对哺乳动物来说, 鸟巢蕨是东南亚地区斑翅果蝠(Balionycteris maculata)搭建繁殖巢的理想场所, 增加了果蝠的繁殖成功率(Hodgkison et al., 2003). ...

An investigation of two bromeliad myrmecophytes: Tillandsia butzii Mez, T. caput-medusae E. Morren, and their ants

2

1970

... Representative families, genera, distribution and the specialized organs of ant-house epiphytes

Table 4 | 科 Family | 属 Genus | 特化器官 Specialized organ | 分布地 Distribution | 参考文献 Reference |

茜草科

Rubiaceae | Myrmecodia | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Kapitany, 2008 |

| Hydnophytum | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Kapitany, 2008 |

| Squamellaria | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 大洋洲

Oceania | Chomicki & Renner, 2019 |

夹竹桃科

Apocynaceae | 眼树莲属 Dischidia | 特化叶

Special leaves | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Treseder et al., 1995 |

水龙骨科

Polypodiaceae | Lecanopteris | 中空根状茎

Hollow rhizome | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Gay, 1991 |

兰科

Orchidaceae | 鹿角蕨属 Platycerium | 叶包鞘

Leaf sheath | 东南亚

Southeast Asia | Franken & Roos, 1982 |

| Microgramma | 中空的侧根状囊

Hollow lateral root sac | 南美洲

South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| Caularthron | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Fisher et al., 1990 |

凤梨科

Bromeliaceae | Myrmecophila | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Fisher et al., 1990 |

| Schomburgkia | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Rico-Gray & Thien, 1989 |

| Dimerandra | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Stuntz et al., 2002 |

| Tillandsia | 叶基部扩宽

Leaf base widening | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Benzing, 1970 |

2 附生植物生境营建作用的生态学功能 2.1 提升生态系统物种多样性附生植物营建的生境对生态系统物种多样性具有积极影响, 收集型植物及其收集物在林冠中营建了难能可贵的类地表环境, 为诸多无法适应林冠暴晒、缺水等逆境的生物提供了必要的生境(Ortega- Solís et al, 2017).分布广泛的收集型植物及其营建的特殊生境在不同大洲的热带地区发挥着相似的生态功能, 支持了各地区生物类群在林冠中的生存.多项研究均指出, 收集型植物是局域尺度上非常重要的伞护种(umbrella species), 在生物多样性保护、生态过程和生态系统生态学研究中具有重要的意义, 值得加强研究和保护(Karasawa & Hijii, 2006; Phillips et al., 2020). ...

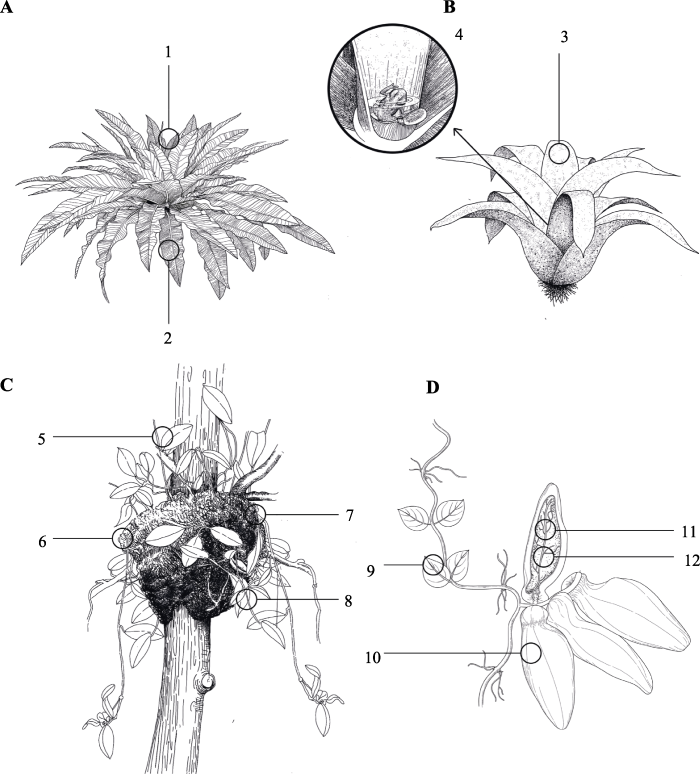

... 新热带区的兰科的Caularthron、Myrmecophila、Schomburgkia和Dimerandra等属植物, 其部分假鳞茎会自然发育成内部中空, 仅在基部留有一个开口的形态, 以适宜蚂蚁居住(Fisher et al., 1990) (图1D).这些植物能够收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑并从碎屑中获得氮素(Gegenbauer et al., 2012), 有蚂蚁居住的植株可获得更加充足的养分, 产生更多的芽和果(Fisher, 1992).而为了更大限度地吸引蚂蚁前来居住, 兰科植物还常常提供花外蜜作为蚂蚁的食物(Fisher & Zimmerman, 1988).南美洲的Microgramma bifrons通过演化出中空的囊状侧根吸引蚂蚁居住(Davidson & Epstein, 1989).凤梨科Tillandsia属植物在加宽的叶基之间有空腔, 蚂蚁可以通过穿孔方式进入这些空腔定居(Benzing, 1970). ...

7

2008

... 为克服林冠缺乏养分和水分的极端环境, 收集型植物具有伸展的叶片, 形成篮状或兜状结构, 可以收集林冠层掉落下来的枯枝落叶和动物残骸, 也能够收集和保存大量的水分.这些被收集在特化结构中的生物残骸, 可以在热带雨林高温高湿的条件下快速分解, 为附生植物提供营养(Benzing, 2008).因此, 这类植物也被冠以“营养海盗”、植物界的“滤食者”之名(Zona & Christenhusz, 2015; Zotz, 2016).收集型植物广泛存在于全球热带地区, 旧热带区以水龙骨科、铁角蕨科和部分兰科植物为主; 新热带区以凤梨科、天南星科和兰科植物为主. ...

... 根据主要收集物的不同, 收集型植物可被分为收集枯枝败叶等固体物为主的篮式植物(trash- basket plant)和收集水分为主的水箱植物(tank forms plant) (Benzing, 2008), 两者在生境营建和共存物种方面都存在着极大的不同. ...

... 凤梨科附生植物演化出一条与篮式植物类似, 但更加强调水分保存的路线, 被称为水箱附生植物或水箱凤梨(tank bromeliads) (Spicer & Woods, 2022).其依靠莲座式排列的革质叶片组成贮水器, 在林冠的间歇性供水中储存雨水, 形成空中水池(图1B), 该演化特征大大提升了凤梨科植物的适应能力, 加之叶片具有吸收性毛状体、CAM途径以及鸟类传粉等一系列适应特征, 极大地拓宽了凤梨科植物的适应范围和生态位, 使其成为附生植物中多样性仅次于兰科的第二大类群(Benzing, 2008). ...

... 蚂蚁作为热带地区无脊椎动物中的绝对优势种, 凭借其高度社会化的劳动分工以及全年活动的特征, 对生态系统有着巨大的影响力, 很可能是促使部分植物演化的重要推动力(Rowe, 2012).在林冠中, 筑巢空间与食物是影响蚂蚁种群的重要因素(Blüthgen & Feldhaar, 2009).附生植物与蚂蚁之间需求的互补, 使两者之间演化出了多种形式的共生关系(Benzing, 2008), 这些共生关系的主要内核便在于: 附生植物可为蚂蚁提供食物以及适宜的栖息空间, 而作为回报, 蚂蚁为附生植物提供保护, 同时蚂蚁活动产生的有机物碎屑也是部分植物类群重要的养分来源(Blüthgen & Feldhaar, 2009).从生境营建的层面来说, 附生植物与蚂蚁拥有两种极为特别的共生模式: 蚂蚁花园(ant-gardens)和蚁栖(ant-house)植物(Zotz, 2016). ...

... 由水箱凤梨特殊贮水器营建的空中水池对许多林冠生物来说是不可或缺的水生生境, 其对新热带森林生态系统的重要性甚至高于大型鸟巢蕨之于旧热带区森林生态系统(Zotz, 2016).在哥伦比亚的云雾林中, 每hm2地域内的水箱凤梨可蓄水5万L, 且每个大型水箱凤梨都能创造出高质量的生境, 足以支持一个微型水生生态系统(Benzing, 2008).水箱凤梨庇护了大量节肢动物, 对哥斯达黎加130份水箱凤梨进行样本监测, 发现了470种节肢动物, 其中大部分为双翅目的各种蚊类和蛛形纲的捕食性动物(Ochoa et al., 1993).水箱凤梨为诸如卵齿蟾科、雨蛙科、箭毒蛙科等蛙类提供了必要的生存环境(Benzing & Bennett, 2000; Mccracken & Forstner, 2014).这些蛙类可以在一天中最热、最干燥的时候依赖水箱凤梨获得阴湿环境(Benzing, 2008), 繁殖季在凤梨中产卵, 孵化后的蝌蚪在水箱中生长发育.与蛙类相似, 生活在美洲的有尾目蝾螈类动物也十分依赖水箱凤梨的庇护, 在中美洲部分地区几乎一半的水箱凤梨中都有蝾螈居住.此外, 还存在一些蜥蜴与蛇类居住于水箱凤梨中的案例, 但随机性较强(Mccracken & Forstner, 2014).除动物外, 水生的狸藻科食虫植物, 如Utricularia humboldtii也会在水箱凤梨中生长(Benzing, 2008).新热带地区广泛分布的水箱凤梨增加了雨林中物种的多样性(Brouard et al., 2012), 因此被称为新热带生态系统中的“生物多样性扩增器” (Thiago et al., 2010). ...

... ).这些蛙类可以在一天中最热、最干燥的时候依赖水箱凤梨获得阴湿环境(Benzing, 2008), 繁殖季在凤梨中产卵, 孵化后的蝌蚪在水箱中生长发育.与蛙类相似, 生活在美洲的有尾目蝾螈类动物也十分依赖水箱凤梨的庇护, 在中美洲部分地区几乎一半的水箱凤梨中都有蝾螈居住.此外, 还存在一些蜥蜴与蛇类居住于水箱凤梨中的案例, 但随机性较强(Mccracken & Forstner, 2014).除动物外, 水生的狸藻科食虫植物, 如Utricularia humboldtii也会在水箱凤梨中生长(Benzing, 2008).新热带地区广泛分布的水箱凤梨增加了雨林中物种的多样性(Brouard et al., 2012), 因此被称为新热带生态系统中的“生物多样性扩增器” (Thiago et al., 2010). ...

... 也会在水箱凤梨中生长(Benzing, 2008).新热带地区广泛分布的水箱凤梨增加了雨林中物种的多样性(Brouard et al., 2012), 因此被称为新热带生态系统中的“生物多样性扩增器” (Thiago et al., 2010). ...

6

2000

... Bromeliads plants with tank structure and animals living inside

Table 2 亚科

Subfamily | 属

Genus | 分布

Distribution | 主要共存动物(纲)

Main coexisting fauna (class) | 参考文献

Reference |

沙漠凤梨亚科

Pitcairnioideae | Brocchinia | 南美洲 South America | P | Givnish et al.,1984 |

凤梨亚科

Bromelioideae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A-N, P-T | Freire et al., 2021 |

| Androlepis | 中美洲 Central America | F | Fragoso & Rojas-Fernández, 1996 |

| Araeococcus | 中美洲 Central America | P | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| 水塔花属 Billbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

| Canistrum | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Hohenbergia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Lymania | 中美洲 Central America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Neoregelia | 中美洲 Central America | A, I, M, P, Q, R | Almeida & Souza, 2020 |

| Ronnbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Nidularium | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

... Benzing & Bennett,

2000 | Neoregelia | 中美洲 Central America | A, I, M, P, Q, R | Almeida & Souza, 2020 |

| Ronnbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Nidularium | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

... Benzing & Bennett,

2000 | Nidularium | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

... 由水箱凤梨特殊贮水器营建的空中水池对许多林冠生物来说是不可或缺的水生生境, 其对新热带森林生态系统的重要性甚至高于大型鸟巢蕨之于旧热带区森林生态系统(Zotz, 2016).在哥伦比亚的云雾林中, 每hm2地域内的水箱凤梨可蓄水5万L, 且每个大型水箱凤梨都能创造出高质量的生境, 足以支持一个微型水生生态系统(Benzing, 2008).水箱凤梨庇护了大量节肢动物, 对哥斯达黎加130份水箱凤梨进行样本监测, 发现了470种节肢动物, 其中大部分为双翅目的各种蚊类和蛛形纲的捕食性动物(Ochoa et al., 1993).水箱凤梨为诸如卵齿蟾科、雨蛙科、箭毒蛙科等蛙类提供了必要的生存环境(Benzing & Bennett, 2000; Mccracken & Forstner, 2014).这些蛙类可以在一天中最热、最干燥的时候依赖水箱凤梨获得阴湿环境(Benzing, 2008), 繁殖季在凤梨中产卵, 孵化后的蝌蚪在水箱中生长发育.与蛙类相似, 生活在美洲的有尾目蝾螈类动物也十分依赖水箱凤梨的庇护, 在中美洲部分地区几乎一半的水箱凤梨中都有蝾螈居住.此外, 还存在一些蜥蜴与蛇类居住于水箱凤梨中的案例, 但随机性较强(Mccracken & Forstner, 2014).除动物外, 水生的狸藻科食虫植物, 如Utricularia humboldtii也会在水箱凤梨中生长(Benzing, 2008).新热带地区广泛分布的水箱凤梨增加了雨林中物种的多样性(Brouard et al., 2012), 因此被称为新热带生态系统中的“生物多样性扩增器” (Thiago et al., 2010). ...

... 收集型植物对于小型无脊椎动物丰度的提升也进一步提升了鸟类获取食物的效率(Cestari, 2009), 水箱凤梨是鸟类访问频率最高的一类附生植物, 除了花蜜和果实这些直接吸引鸟类的资源, 水箱凤梨内部包含大量无脊椎动物、两栖动物, 是鸟类搜寻食物的热点地区, 分布于南美的鹤鹰(Geranospiza caerulescens)通过长腿和异常灵活的跗骨关节, 可以高效地捕获水箱凤梨中的动物(Benzing & Bennett, 2000).附生植物所营建的生境使食物网结构更加多元化, 增加了群落的稳定性. ...

... 不同水箱凤梨的贮水池之间具有不同的理化特性, 甚至含有某些特定物质, 由此产生的生境异质性, 提升了所庇护的原生生物和小型后生动物类群的多样性(Foissner et al., 2003).原生生物纤毛虫(Ciliophora spp.)是生态系统中参与营养循环和控制细菌种群的重要组成部分, 水箱凤梨为纤毛虫提供了一个林冠之上广泛分布的生存空间(Foissner et al., 2003).由于干旱时期水箱内空间和资源减少, 水箱构成一个高度竞争的微生态系统, 而竞争和隔离对居住其中的纤毛虫物种的形成和分化起到了重要作用(Durán-Ramírez et al., 2015).目前在水箱凤梨中已发现170种纤毛虫, 其中16种为水箱特有种(Durán- Ramírez et al., 2020).水箱凤梨在两栖动物这类易受干旱影响的小型脊椎动物演化过程中扮演了决定性的角色, 为适应水箱内部构造, 一些蝌蚪特化出异常纤细的身体, 以适应紧密重叠的凤梨叶基构成的狭窄空间(Benzing & Bennett, 2000).部分仅生活在水箱之中的蝾螈为了适应水箱内部环境, 特化出较小的躯干(约50 mm长), 细长的尾及四肢, 分开的趾以及正面定向的眼睛(Ruano-Fajardo et al., 2014). ...

Positive interactions in communities

1

1994

... 胁迫梯度假说预测了不同植物之间在低资源、高胁迫环境中更倾向于采取正相互作用以助于彼此的生存和繁殖(Bertness & Callaway, 1994).在林冠环境中, 附生植物之间的密切物理联系有利于改善干旱的胁迫, 因此在低密度状态下附生植物通常都表现出不同程度的互惠作用(Spicer & Woods, 2022), 如凤梨科交织的根系可以帮助捕捉其他附生植物随风传播的种子并有助于其萌发(Chaves & Rossatto, 2020); 大鳞巢蕨(A. antiquum)为附生在下方的Haplopteris zosterifolia提供了较为稳定的水分供给(Jian et al., 2013).随着附生植物密度的不断上升, 当达到某一临界值后种间关系可能由互惠转向竞争, 由于大多数附生植物在林冠中的分布都相对松散, 因此竞争是否会对附生植物多样性、丰度或群落聚集模式产生显著影响还存在争议(Spicer & Woods, 2022), 未来的研究应从更宏观且动态的角度进行探究, 依靠林冠塔吊等现代化科研设施, 对整个片区的附生植物进行长期监测, 分析附生植物的空间分布以及群落结构的动态变化, 以此探究附生植物种间种内各种形式的相互作用及其产生的影响. ...

3

2009

... 蚂蚁作为热带地区无脊椎动物中的绝对优势种, 凭借其高度社会化的劳动分工以及全年活动的特征, 对生态系统有着巨大的影响力, 很可能是促使部分植物演化的重要推动力(Rowe, 2012).在林冠中, 筑巢空间与食物是影响蚂蚁种群的重要因素(Blüthgen & Feldhaar, 2009).附生植物与蚂蚁之间需求的互补, 使两者之间演化出了多种形式的共生关系(Benzing, 2008), 这些共生关系的主要内核便在于: 附生植物可为蚂蚁提供食物以及适宜的栖息空间, 而作为回报, 蚂蚁为附生植物提供保护, 同时蚂蚁活动产生的有机物碎屑也是部分植物类群重要的养分来源(Blüthgen & Feldhaar, 2009).从生境营建的层面来说, 附生植物与蚂蚁拥有两种极为特别的共生模式: 蚂蚁花园(ant-gardens)和蚁栖(ant-house)植物(Zotz, 2016). ...

... ), 这些共生关系的主要内核便在于: 附生植物可为蚂蚁提供食物以及适宜的栖息空间, 而作为回报, 蚂蚁为附生植物提供保护, 同时蚂蚁活动产生的有机物碎屑也是部分植物类群重要的养分来源(Blüthgen & Feldhaar, 2009).从生境营建的层面来说, 附生植物与蚂蚁拥有两种极为特别的共生模式: 蚂蚁花园(ant-gardens)和蚁栖(ant-house)植物(Zotz, 2016). ...

... 自然界中, 仅有部分树栖蚁能够自己建造巢穴(如上文蚂蚁花园中的蚂蚁), 大多树栖蚁只能依靠植物上自然形成的洞穴筑巢, 导致筑巢空间成为树栖蚁的紧缺资源(Blüthgen & Feldhaar, 2009).在附生植物与蚂蚁的协同演化过程中, 出现了一类附生蚁栖植物, 它们通过特化自身某一部位器官, 使其适宜蚂蚁居住.作为回报, 该类植物可依靠蚂蚁防御植食性动物, 同时利用蚂蚁修剪其他植物的枝条, 抑制竞争性植物的侵扰(张霜等, 2010).部分附生蚁栖植物还可收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑, 吸收其中的养分(Zotz, 2016; 王亮等, 2020), 因此这类植物也被称作蚁养植物(ant-fed plants) (Rico-Gray & Oliveira, 2008). ...

Ants as epiphyte gardeners: comparing the nutrient quality of ant and termite canopy substrates in a Venezuelan lowland rain forest

3

2001

... Representative families, genera, and the major distribution areas of ant-garden epiphyte species

Table 3 | 科 Family | 属 Genus | 分布地 Distribution | 参考文献 Reference |

| 夹竹桃科 Apocynaceae | 眼树莲属 Dischidia | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| Hoya | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 苦苣苔科 Gesneriaceae | 芒毛苣苔属 Aeschynanthus | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann & Maschwitz, 2006 |

| Codonanthe | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Blüthgen et al., 2001 |

| Columnea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Orivel & Leroy, 2011 |

| 野牡丹科 Melastomataceae | 酸脚杆属 Medinilla | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 厚距花属 Pachycentria | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 桑科 Moraceae | 榕属 Ficus | 东南亚、中美洲、南美洲

Southeast Asia, Central, South America | Kaufmann, 2002; Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| 荨麻科 Urticaceae | 锥头麻属 Poikilospermum | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann & Maschwitz, 2006; Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 姜科 Zingiberaceae | 姜花属 Hedychium | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 天南星科 Araceae | 花烛属 Anthurium | 南美洲 South America | Blüthgen et al., 2001 |

| 喜林芋属 Philodendron | 南美洲 South America | Schmit-Neuerburg & Blüthgen, 2007;

Blüthgen et al., 2001 |

| 凤梨科 Bromeliaceae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| Neoregelia | 南美洲 South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| Streptocalyx | 南美洲 South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| 仙人掌科 Cactaceae | 昙花属 Epiphyllum | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Schmit-Neuerburg & Blüthgen, 2007 |

| 兰科 Orchidaceae | Coryanthes | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| Epidendrum | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| 胡椒科 Piperaceae | 草胡椒属 Peperomia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Youngsteadt et al., 2009 |

| 茄科 Solanaceae | Markea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Dejean et al., 2000 |

1.2.2 蚁栖植物自然界中, 仅有部分树栖蚁能够自己建造巢穴(如上文蚂蚁花园中的蚂蚁), 大多树栖蚁只能依靠植物上自然形成的洞穴筑巢, 导致筑巢空间成为树栖蚁的紧缺资源(Blüthgen & Feldhaar, 2009).在附生植物与蚂蚁的协同演化过程中, 出现了一类附生蚁栖植物, 它们通过特化自身某一部位器官, 使其适宜蚂蚁居住.作为回报, 该类植物可依靠蚂蚁防御植食性动物, 同时利用蚂蚁修剪其他植物的枝条, 抑制竞争性植物的侵扰(张霜等, 2010).部分附生蚁栖植物还可收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑, 吸收其中的养分(Zotz, 2016; 王亮等, 2020), 因此这类植物也被称作蚁养植物(ant-fed plants) (Rico-Gray & Oliveira, 2008). ...

... .,

2001 | 喜林芋属 Philodendron | 南美洲 South America | Schmit-Neuerburg & Blüthgen, 2007;

Blüthgen et al., 2001 |

| 凤梨科 Bromeliaceae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| Neoregelia | 南美洲 South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| Streptocalyx | 南美洲 South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| 仙人掌科 Cactaceae | 昙花属 Epiphyllum | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Schmit-Neuerburg & Blüthgen, 2007 |

| 兰科 Orchidaceae | Coryanthes | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| Epidendrum | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| 胡椒科 Piperaceae | 草胡椒属 Peperomia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Youngsteadt et al., 2009 |

| 茄科 Solanaceae | Markea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Dejean et al., 2000 |

1.2.2 蚁栖植物自然界中, 仅有部分树栖蚁能够自己建造巢穴(如上文蚂蚁花园中的蚂蚁), 大多树栖蚁只能依靠植物上自然形成的洞穴筑巢, 导致筑巢空间成为树栖蚁的紧缺资源(Blüthgen & Feldhaar, 2009).在附生植物与蚂蚁的协同演化过程中, 出现了一类附生蚁栖植物, 它们通过特化自身某一部位器官, 使其适宜蚂蚁居住.作为回报, 该类植物可依靠蚂蚁防御植食性动物, 同时利用蚂蚁修剪其他植物的枝条, 抑制竞争性植物的侵扰(张霜等, 2010).部分附生蚁栖植物还可收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑, 吸收其中的养分(Zotz, 2016; 王亮等, 2020), 因此这类植物也被称作蚁养植物(ant-fed plants) (Rico-Gray & Oliveira, 2008). ...

... .,

2001 | 凤梨科 Bromeliaceae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| Neoregelia | 南美洲 South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| Streptocalyx | 南美洲 South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| 仙人掌科 Cactaceae | 昙花属 Epiphyllum | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Schmit-Neuerburg & Blüthgen, 2007 |

| 兰科 Orchidaceae | Coryanthes | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| Epidendrum | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| 胡椒科 Piperaceae | 草胡椒属 Peperomia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Youngsteadt et al., 2009 |

| 茄科 Solanaceae | Markea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Dejean et al., 2000 |

1.2.2 蚁栖植物自然界中, 仅有部分树栖蚁能够自己建造巢穴(如上文蚂蚁花园中的蚂蚁), 大多树栖蚁只能依靠植物上自然形成的洞穴筑巢, 导致筑巢空间成为树栖蚁的紧缺资源(Blüthgen & Feldhaar, 2009).在附生植物与蚂蚁的协同演化过程中, 出现了一类附生蚁栖植物, 它们通过特化自身某一部位器官, 使其适宜蚂蚁居住.作为回报, 该类植物可依靠蚂蚁防御植食性动物, 同时利用蚂蚁修剪其他植物的枝条, 抑制竞争性植物的侵扰(张霜等, 2010).部分附生蚁栖植物还可收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑, 吸收其中的养分(Zotz, 2016; 王亮等, 2020), 因此这类植物也被称作蚁养植物(ant-fed plants) (Rico-Gray & Oliveira, 2008). ...

Understorey environments influence functional diversity in tank-bromeliad ecosystems

1

2012

... 由水箱凤梨特殊贮水器营建的空中水池对许多林冠生物来说是不可或缺的水生生境, 其对新热带森林生态系统的重要性甚至高于大型鸟巢蕨之于旧热带区森林生态系统(Zotz, 2016).在哥伦比亚的云雾林中, 每hm2地域内的水箱凤梨可蓄水5万L, 且每个大型水箱凤梨都能创造出高质量的生境, 足以支持一个微型水生生态系统(Benzing, 2008).水箱凤梨庇护了大量节肢动物, 对哥斯达黎加130份水箱凤梨进行样本监测, 发现了470种节肢动物, 其中大部分为双翅目的各种蚊类和蛛形纲的捕食性动物(Ochoa et al., 1993).水箱凤梨为诸如卵齿蟾科、雨蛙科、箭毒蛙科等蛙类提供了必要的生存环境(Benzing & Bennett, 2000; Mccracken & Forstner, 2014).这些蛙类可以在一天中最热、最干燥的时候依赖水箱凤梨获得阴湿环境(Benzing, 2008), 繁殖季在凤梨中产卵, 孵化后的蝌蚪在水箱中生长发育.与蛙类相似, 生活在美洲的有尾目蝾螈类动物也十分依赖水箱凤梨的庇护, 在中美洲部分地区几乎一半的水箱凤梨中都有蝾螈居住.此外, 还存在一些蜥蜴与蛇类居住于水箱凤梨中的案例, 但随机性较强(Mccracken & Forstner, 2014).除动物外, 水生的狸藻科食虫植物, 如Utricularia humboldtii也会在水箱凤梨中生长(Benzing, 2008).新热带地区广泛分布的水箱凤梨增加了雨林中物种的多样性(Brouard et al., 2012), 因此被称为新热带生态系统中的“生物多样性扩增器” (Thiago et al., 2010). ...

Mosquitoes in bromeliads at ground level of the Brazilian Atlantic forest: the relationship between mosquito fauna, water volume, and plant type

2

2015

... Bromeliads plants with tank structure and animals living inside

Table 2 亚科

Subfamily | 属

Genus | 分布

Distribution | 主要共存动物(纲)

Main coexisting fauna (class) | 参考文献

Reference |

沙漠凤梨亚科

Pitcairnioideae | Brocchinia | 南美洲 South America | P | Givnish et al.,1984 |

凤梨亚科

Bromelioideae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A-N, P-T | Freire et al., 2021 |

| Androlepis | 中美洲 Central America | F | Fragoso & Rojas-Fernández, 1996 |

| Araeococcus | 中美洲 Central America | P | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| 水塔花属 Billbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

| Canistrum | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Hohenbergia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Lymania | 中美洲 Central America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Neoregelia | 中美洲 Central America | A, I, M, P, Q, R | Almeida & Souza, 2020 |

| Ronnbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Nidularium | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

... .,

2015 空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

Epiphyte plants use by birds in Brazil

1

2009

... 收集型植物对于小型无脊椎动物丰度的提升也进一步提升了鸟类获取食物的效率(Cestari, 2009), 水箱凤梨是鸟类访问频率最高的一类附生植物, 除了花蜜和果实这些直接吸引鸟类的资源, 水箱凤梨内部包含大量无脊椎动物、两栖动物, 是鸟类搜寻食物的热点地区, 分布于南美的鹤鹰(Geranospiza caerulescens)通过长腿和异常灵活的跗骨关节, 可以高效地捕获水箱凤梨中的动物(Benzing & Bennett, 2000).附生植物所营建的生境使食物网结构更加多元化, 增加了群落的稳定性. ...

Unravelling intricate interactions among atmospheric bromeliads with highly overlapping niches in seasonal systems

1

2020

... 胁迫梯度假说预测了不同植物之间在低资源、高胁迫环境中更倾向于采取正相互作用以助于彼此的生存和繁殖(Bertness & Callaway, 1994).在林冠环境中, 附生植物之间的密切物理联系有利于改善干旱的胁迫, 因此在低密度状态下附生植物通常都表现出不同程度的互惠作用(Spicer & Woods, 2022), 如凤梨科交织的根系可以帮助捕捉其他附生植物随风传播的种子并有助于其萌发(Chaves & Rossatto, 2020); 大鳞巢蕨(A. antiquum)为附生在下方的Haplopteris zosterifolia提供了较为稳定的水分供给(Jian et al., 2013).随着附生植物密度的不断上升, 当达到某一临界值后种间关系可能由互惠转向竞争, 由于大多数附生植物在林冠中的分布都相对松散, 因此竞争是否会对附生植物多样性、丰度或群落聚集模式产生显著影响还存在争议(Spicer & Woods, 2022), 未来的研究应从更宏观且动态的角度进行探究, 依靠林冠塔吊等现代化科研设施, 对整个片区的附生植物进行长期监测, 分析附生植物的空间分布以及群落结构的动态变化, 以此探究附生植物种间种内各种形式的相互作用及其产生的影响. ...

Farming by ants remodels nutrient uptake in epiphytes

2

2019

... Representative families, genera, distribution and the specialized organs of ant-house epiphytes

Table 4 | 科 Family | 属 Genus | 特化器官 Specialized organ | 分布地 Distribution | 参考文献 Reference |

茜草科

Rubiaceae | Myrmecodia | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Kapitany, 2008 |

| Hydnophytum | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Kapitany, 2008 |

| Squamellaria | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 大洋洲

Oceania | Chomicki & Renner, 2019 |

夹竹桃科

Apocynaceae | 眼树莲属 Dischidia | 特化叶

Special leaves | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Treseder et al., 1995 |

水龙骨科

Polypodiaceae | Lecanopteris | 中空根状茎

Hollow rhizome | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Gay, 1991 |

兰科

Orchidaceae | 鹿角蕨属 Platycerium | 叶包鞘

Leaf sheath | 东南亚

Southeast Asia | Franken & Roos, 1982 |

| Microgramma | 中空的侧根状囊

Hollow lateral root sac | 南美洲

South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| Caularthron | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Fisher et al., 1990 |

凤梨科

Bromeliaceae | Myrmecophila | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Fisher et al., 1990 |

| Schomburgkia | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Rico-Gray & Thien, 1989 |

| Dimerandra | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Stuntz et al., 2002 |

| Tillandsia | 叶基部扩宽

Leaf base widening | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Benzing, 1970 |

2 附生植物生境营建作用的生态学功能 2.1 提升生态系统物种多样性附生植物营建的生境对生态系统物种多样性具有积极影响, 收集型植物及其收集物在林冠中营建了难能可贵的类地表环境, 为诸多无法适应林冠暴晒、缺水等逆境的生物提供了必要的生境(Ortega- Solís et al, 2017).分布广泛的收集型植物及其营建的特殊生境在不同大洲的热带地区发挥着相似的生态功能, 支持了各地区生物类群在林冠中的生存.多项研究均指出, 收集型植物是局域尺度上非常重要的伞护种(umbrella species), 在生物多样性保护、生态过程和生态系统生态学研究中具有重要的意义, 值得加强研究和保护(Karasawa & Hijii, 2006; Phillips et al., 2020). ...

... 在资源相对匮乏的林冠环境, 动物活动产生的有机物对附生植物来说是十分重要的养分来源, 通过为动物提供适宜生境使其长期在附生植物营养吸收范围内活动, 对双方适合度的提升都有帮助.关于蚂蚁与附生植物共生关系的研究由来已久, 最新的一项研究揭示了蚂蚁与附生植物之间存在栽培者与作物的关系, 在斐济茜草科Squamellaria属蚁栖植物的研究中观察到蚂蚁中存在特定分工类群, 专门负责为Squamellaria属植物内部的吸收性疣状体供给营养, 蚂蚁通过喂养它们以增加蚁巢的规模(Chomicki & Renner, 2019).这为后续的研究提供了一个非常有趣的思路, 部分蚁巢型附生植物可能是被蚂蚁驯化的一类特殊“作物”.而对于收集型植物来说, 共生动物在营养方面的贡献除了提供有机产物外, 分解枯枝落叶也十分重要, 为此收集型植物中常常有蚯蚓、马陆之类的分解者.然而这些行动能力较弱的分解者如何在林冠中分散生长的收集型植物之间扩散还是一个值得探究的问题. ...

6

1989

... 目前, 蚂蚁花园在热带美洲与东南亚地区均有报道, 主要分布于10° N至10° S之间, 随纬度升高逐渐减少(Kaufmann & Maschwitz, 2006), 花园的形成是蚂蚁与附生植物长期协同演化的产物, 具有高度的复杂性与专一性, 以至于许多该类植物仅能生长在蚂蚁花园系统中(Davidson & Epstein, 1989).蚂蚁花园植物主要有12科20属(表3); 其中新热带区主要有天南星科、凤梨科、仙人掌科、兰科、胡椒科和茄科6个科; 旧热带区主要有夹竹桃科、野牡丹科、姜科和荨麻科4个科; 而苦苣苔科与桑科在新旧热带均有分布(Orivel & Leroy, 2011). ...

... Representative families, genera, and the major distribution areas of ant-garden epiphyte species

Table 3 | 科 Family | 属 Genus | 分布地 Distribution | 参考文献 Reference |

| 夹竹桃科 Apocynaceae | 眼树莲属 Dischidia | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| Hoya | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 苦苣苔科 Gesneriaceae | 芒毛苣苔属 Aeschynanthus | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann & Maschwitz, 2006 |

| Codonanthe | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Blüthgen et al., 2001 |

| Columnea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Orivel & Leroy, 2011 |

| 野牡丹科 Melastomataceae | 酸脚杆属 Medinilla | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 厚距花属 Pachycentria | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 桑科 Moraceae | 榕属 Ficus | 东南亚、中美洲、南美洲

Southeast Asia, Central, South America | Kaufmann, 2002; Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| 荨麻科 Urticaceae | 锥头麻属 Poikilospermum | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann & Maschwitz, 2006; Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 姜科 Zingiberaceae | 姜花属 Hedychium | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 天南星科 Araceae | 花烛属 Anthurium | 南美洲 South America | Blüthgen et al., 2001 |

| 喜林芋属 Philodendron | 南美洲 South America | Schmit-Neuerburg & Blüthgen, 2007;

Blüthgen et al., 2001 |

| 凤梨科 Bromeliaceae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| Neoregelia | 南美洲 South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| Streptocalyx | 南美洲 South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| 仙人掌科 Cactaceae | 昙花属 Epiphyllum | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Schmit-Neuerburg & Blüthgen, 2007 |

| 兰科 Orchidaceae | Coryanthes | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| Epidendrum | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| 胡椒科 Piperaceae | 草胡椒属 Peperomia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Youngsteadt et al., 2009 |

| 茄科 Solanaceae | Markea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Dejean et al., 2000 |

1.2.2 蚁栖植物自然界中, 仅有部分树栖蚁能够自己建造巢穴(如上文蚂蚁花园中的蚂蚁), 大多树栖蚁只能依靠植物上自然形成的洞穴筑巢, 导致筑巢空间成为树栖蚁的紧缺资源(Blüthgen & Feldhaar, 2009).在附生植物与蚂蚁的协同演化过程中, 出现了一类附生蚁栖植物, 它们通过特化自身某一部位器官, 使其适宜蚂蚁居住.作为回报, 该类植物可依靠蚂蚁防御植食性动物, 同时利用蚂蚁修剪其他植物的枝条, 抑制竞争性植物的侵扰(张霜等, 2010).部分附生蚁栖植物还可收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑, 吸收其中的养分(Zotz, 2016; 王亮等, 2020), 因此这类植物也被称作蚁养植物(ant-fed plants) (Rico-Gray & Oliveira, 2008). ...

... Davidson & Epstein,

1989 | Streptocalyx | 南美洲 South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| 仙人掌科 Cactaceae | 昙花属 Epiphyllum | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Schmit-Neuerburg & Blüthgen, 2007 |

| 兰科 Orchidaceae | Coryanthes | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| Epidendrum | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| 胡椒科 Piperaceae | 草胡椒属 Peperomia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Youngsteadt et al., 2009 |

| 茄科 Solanaceae | Markea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Dejean et al., 2000 |

1.2.2 蚁栖植物自然界中, 仅有部分树栖蚁能够自己建造巢穴(如上文蚂蚁花园中的蚂蚁), 大多树栖蚁只能依靠植物上自然形成的洞穴筑巢, 导致筑巢空间成为树栖蚁的紧缺资源(Blüthgen & Feldhaar, 2009).在附生植物与蚂蚁的协同演化过程中, 出现了一类附生蚁栖植物, 它们通过特化自身某一部位器官, 使其适宜蚂蚁居住.作为回报, 该类植物可依靠蚂蚁防御植食性动物, 同时利用蚂蚁修剪其他植物的枝条, 抑制竞争性植物的侵扰(张霜等, 2010).部分附生蚁栖植物还可收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑, 吸收其中的养分(Zotz, 2016; 王亮等, 2020), 因此这类植物也被称作蚁养植物(ant-fed plants) (Rico-Gray & Oliveira, 2008). ...

... Davidson & Epstein,

1989 | 仙人掌科 Cactaceae | 昙花属 Epiphyllum | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Schmit-Neuerburg & Blüthgen, 2007 |

| 兰科 Orchidaceae | Coryanthes | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| Epidendrum | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| 胡椒科 Piperaceae | 草胡椒属 Peperomia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Youngsteadt et al., 2009 |

| 茄科 Solanaceae | Markea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Dejean et al., 2000 |

1.2.2 蚁栖植物自然界中, 仅有部分树栖蚁能够自己建造巢穴(如上文蚂蚁花园中的蚂蚁), 大多树栖蚁只能依靠植物上自然形成的洞穴筑巢, 导致筑巢空间成为树栖蚁的紧缺资源(Blüthgen & Feldhaar, 2009).在附生植物与蚂蚁的协同演化过程中, 出现了一类附生蚁栖植物, 它们通过特化自身某一部位器官, 使其适宜蚂蚁居住.作为回报, 该类植物可依靠蚂蚁防御植食性动物, 同时利用蚂蚁修剪其他植物的枝条, 抑制竞争性植物的侵扰(张霜等, 2010).部分附生蚁栖植物还可收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑, 吸收其中的养分(Zotz, 2016; 王亮等, 2020), 因此这类植物也被称作蚁养植物(ant-fed plants) (Rico-Gray & Oliveira, 2008). ...

... Representative families, genera, distribution and the specialized organs of ant-house epiphytes

Table 4 | 科 Family | 属 Genus | 特化器官 Specialized organ | 分布地 Distribution | 参考文献 Reference |

茜草科

Rubiaceae | Myrmecodia | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Kapitany, 2008 |

| Hydnophytum | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Kapitany, 2008 |

| Squamellaria | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 大洋洲

Oceania | Chomicki & Renner, 2019 |

夹竹桃科

Apocynaceae | 眼树莲属 Dischidia | 特化叶

Special leaves | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Treseder et al., 1995 |

水龙骨科

Polypodiaceae | Lecanopteris | 中空根状茎

Hollow rhizome | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Gay, 1991 |

兰科

Orchidaceae | 鹿角蕨属 Platycerium | 叶包鞘

Leaf sheath | 东南亚

Southeast Asia | Franken & Roos, 1982 |

| Microgramma | 中空的侧根状囊

Hollow lateral root sac | 南美洲

South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| Caularthron | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Fisher et al., 1990 |

凤梨科

Bromeliaceae | Myrmecophila | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Fisher et al., 1990 |

| Schomburgkia | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Rico-Gray & Thien, 1989 |

| Dimerandra | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Stuntz et al., 2002 |

| Tillandsia | 叶基部扩宽

Leaf base widening | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Benzing, 1970 |

2 附生植物生境营建作用的生态学功能 2.1 提升生态系统物种多样性附生植物营建的生境对生态系统物种多样性具有积极影响, 收集型植物及其收集物在林冠中营建了难能可贵的类地表环境, 为诸多无法适应林冠暴晒、缺水等逆境的生物提供了必要的生境(Ortega- Solís et al, 2017).分布广泛的收集型植物及其营建的特殊生境在不同大洲的热带地区发挥着相似的生态功能, 支持了各地区生物类群在林冠中的生存.多项研究均指出, 收集型植物是局域尺度上非常重要的伞护种(umbrella species), 在生物多样性保护、生态过程和生态系统生态学研究中具有重要的意义, 值得加强研究和保护(Karasawa & Hijii, 2006; Phillips et al., 2020). ...

... 新热带区的兰科的Caularthron、Myrmecophila、Schomburgkia和Dimerandra等属植物, 其部分假鳞茎会自然发育成内部中空, 仅在基部留有一个开口的形态, 以适宜蚂蚁居住(Fisher et al., 1990) (图1D).这些植物能够收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑并从碎屑中获得氮素(Gegenbauer et al., 2012), 有蚂蚁居住的植株可获得更加充足的养分, 产生更多的芽和果(Fisher, 1992).而为了更大限度地吸引蚂蚁前来居住, 兰科植物还常常提供花外蜜作为蚂蚁的食物(Fisher & Zimmerman, 1988).南美洲的Microgramma bifrons通过演化出中空的囊状侧根吸引蚂蚁居住(Davidson & Epstein, 1989).凤梨科Tillandsia属植物在加宽的叶基之间有空腔, 蚂蚁可以通过穿孔方式进入这些空腔定居(Benzing, 1970). ...

The importance of ant gardens in the pioneer vegetal formations of French Guiana (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

1

2000

... Representative families, genera, and the major distribution areas of ant-garden epiphyte species

Table 3 | 科 Family | 属 Genus | 分布地 Distribution | 参考文献 Reference |

| 夹竹桃科 Apocynaceae | 眼树莲属 Dischidia | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| Hoya | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 苦苣苔科 Gesneriaceae | 芒毛苣苔属 Aeschynanthus | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann & Maschwitz, 2006 |

| Codonanthe | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Blüthgen et al., 2001 |

| Columnea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Orivel & Leroy, 2011 |

| 野牡丹科 Melastomataceae | 酸脚杆属 Medinilla | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 厚距花属 Pachycentria | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 桑科 Moraceae | 榕属 Ficus | 东南亚、中美洲、南美洲

Southeast Asia, Central, South America | Kaufmann, 2002; Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| 荨麻科 Urticaceae | 锥头麻属 Poikilospermum | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann & Maschwitz, 2006; Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 姜科 Zingiberaceae | 姜花属 Hedychium | 东南亚 Southeast Asia | Kaufmann, 2002 |

| 天南星科 Araceae | 花烛属 Anthurium | 南美洲 South America | Blüthgen et al., 2001 |

| 喜林芋属 Philodendron | 南美洲 South America | Schmit-Neuerburg & Blüthgen, 2007;

Blüthgen et al., 2001 |

| 凤梨科 Bromeliaceae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| Neoregelia | 南美洲 South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| Streptocalyx | 南美洲 South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| 仙人掌科 Cactaceae | 昙花属 Epiphyllum | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Schmit-Neuerburg & Blüthgen, 2007 |

| 兰科 Orchidaceae | Coryanthes | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| Epidendrum | 中美洲 Central America | Morales-Linares et al., 2016 |

| 胡椒科 Piperaceae | 草胡椒属 Peperomia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Youngsteadt et al., 2009 |

| 茄科 Solanaceae | Markea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | Dejean et al., 2000 |

1.2.2 蚁栖植物自然界中, 仅有部分树栖蚁能够自己建造巢穴(如上文蚂蚁花园中的蚂蚁), 大多树栖蚁只能依靠植物上自然形成的洞穴筑巢, 导致筑巢空间成为树栖蚁的紧缺资源(Blüthgen & Feldhaar, 2009).在附生植物与蚂蚁的协同演化过程中, 出现了一类附生蚁栖植物, 它们通过特化自身某一部位器官, 使其适宜蚂蚁居住.作为回报, 该类植物可依靠蚂蚁防御植食性动物, 同时利用蚂蚁修剪其他植物的枝条, 抑制竞争性植物的侵扰(张霜等, 2010).部分附生蚁栖植物还可收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑, 吸收其中的养分(Zotz, 2016; 王亮等, 2020), 因此这类植物也被称作蚁养植物(ant-fed plants) (Rico-Gray & Oliveira, 2008). ...

Physical conditions regulate the fungal to bacterial ratios of a tropical suspended soil

1

2017a

... 对收集型植物来说, 微生物在辅助分解有机物方面起到了重要的作用, 而林冠环境温、湿度的极端变化也将筛选适应于环境压力的微生物类群(Donald et al., 2017a).基于DNA测序法的研究表明, 水箱凤梨、林冠腐殖质以及地表土壤三者之间的微生物类群都有显著的差异(Pittl et al., 2010); 基于磷脂脂肪酸法的研究表明, 同一地区的巢蕨高位土与林冠腐殖质中的微生物群落较相似, 不同地区巢蕨中的微生物类群有所不同(Donald et al., 2020).当前的研究认为, 收集型植物高位土中的微生物大多是从当地环境中获取的, 关于其中是否拥有特定微生物类群还需要更多数据支持, 不过这也给未来的研究提供了一个思路, 森林中特定林冠微生物的存在可能是影响收集型植物顺利积累腐殖质的关键因素, 微生物类群的地理分布可能在一定程度上影响收集型植物的扩散.因此, 未来对于热带、亚热带地区孤立次生林的生态修复过程中需要综合考虑林冠微生物起到的重要作用. ...

Colonisation of epiphytic ferns by skinks and geckos in the high canopy of a Bornean rainforest

1

2017b

... 篮式植物在林冠中重建了一个类似地表的高位土环境(Ortega-Solis et al., 2021), 在满足自身养分与水分需求的同时, 为林冠多种生物营建了理想的生境(Beaulieu et al., 2010).许多动物的生长、繁殖都会依赖篮式植物营建的生境(Phillips et al., 2020), 已记录有15纲97科的动物居住于各类篮式植物中, 其中有90科都是无脊椎动物.以鸟巢蕨为例, 加里曼丹岛热带森林中, 林冠中几乎一半的无脊椎动物生物量汇聚于鸟巢蕨中(Ellwood & Foster, 2004), 在日本南部亚热带森林的研究表明, 鸟巢蕨提升了当地无脊椎动物丰度, 并可以为特定物种提供生境, 有助于在亚热带森林尺度上保持无脊椎动物的高物种多样性(Karasawa & Hijii, 2006).除无脊椎动物之外, 鸟巢蕨是蛙类在林冠中重要的生境, 在吕宋岛南部有近1/5的鸟巢蕨被蛙类利用, 尤其是在白天高温之下, 鸟巢蕨的温、湿度的缓冲能力为蛙类创造了理想的避暑空间, 同时潮湿凉爽的内部环境也是蛙类重要的繁殖场所(Scheffers et al., 2014b).在加里曼丹岛人工安置的32株鸟巢蕨中, 半年后均记录到爬行纲的半叶趾虎(Hemiphyllodactylus typus)及Lipinia vittigera在其中栖息并产卵(Donald et al, 2017b).对哺乳动物来说, 鸟巢蕨是东南亚地区斑翅果蝠(Balionycteris maculata)搭建繁殖巢的理想场所, 增加了果蝠的繁殖成功率(Hodgkison et al., 2003). ...

Epiphytic suspended soils from Borneo and Amazonia differ in their microbial community composition

1

2020

... 对收集型植物来说, 微生物在辅助分解有机物方面起到了重要的作用, 而林冠环境温、湿度的极端变化也将筛选适应于环境压力的微生物类群(Donald et al., 2017a).基于DNA测序法的研究表明, 水箱凤梨、林冠腐殖质以及地表土壤三者之间的微生物类群都有显著的差异(Pittl et al., 2010); 基于磷脂脂肪酸法的研究表明, 同一地区的巢蕨高位土与林冠腐殖质中的微生物群落较相似, 不同地区巢蕨中的微生物类群有所不同(Donald et al., 2020).当前的研究认为, 收集型植物高位土中的微生物大多是从当地环境中获取的, 关于其中是否拥有特定微生物类群还需要更多数据支持, 不过这也给未来的研究提供了一个思路, 森林中特定林冠微生物的存在可能是影响收集型植物顺利积累腐殖质的关键因素, 微生物类群的地理分布可能在一定程度上影响收集型植物的扩散.因此, 未来对于热带、亚热带地区孤立次生林的生态修复过程中需要综合考虑林冠微生物起到的重要作用. ...

Checklist of ciliates (Alveolata: Ciliophora) that inhabit in bromeliads from the Neotropical Region

1

2020

... 不同水箱凤梨的贮水池之间具有不同的理化特性, 甚至含有某些特定物质, 由此产生的生境异质性, 提升了所庇护的原生生物和小型后生动物类群的多样性(Foissner et al., 2003).原生生物纤毛虫(Ciliophora spp.)是生态系统中参与营养循环和控制细菌种群的重要组成部分, 水箱凤梨为纤毛虫提供了一个林冠之上广泛分布的生存空间(Foissner et al., 2003).由于干旱时期水箱内空间和资源减少, 水箱构成一个高度竞争的微生态系统, 而竞争和隔离对居住其中的纤毛虫物种的形成和分化起到了重要作用(Durán-Ramírez et al., 2015).目前在水箱凤梨中已发现170种纤毛虫, 其中16种为水箱特有种(Durán- Ramírez et al., 2020).水箱凤梨在两栖动物这类易受干旱影响的小型脊椎动物演化过程中扮演了决定性的角色, 为适应水箱内部构造, 一些蝌蚪特化出异常纤细的身体, 以适应紧密重叠的凤梨叶基构成的狭窄空间(Benzing & Bennett, 2000).部分仅生活在水箱之中的蝾螈为了适应水箱内部环境, 特化出较小的躯干(约50 mm长), 细长的尾及四肢, 分开的趾以及正面定向的眼睛(Ruano-Fajardo et al., 2014). ...

Free-living ciliates from epiphytic tank bromeliads in Mexico

1

2015

... 不同水箱凤梨的贮水池之间具有不同的理化特性, 甚至含有某些特定物质, 由此产生的生境异质性, 提升了所庇护的原生生物和小型后生动物类群的多样性(Foissner et al., 2003).原生生物纤毛虫(Ciliophora spp.)是生态系统中参与营养循环和控制细菌种群的重要组成部分, 水箱凤梨为纤毛虫提供了一个林冠之上广泛分布的生存空间(Foissner et al., 2003).由于干旱时期水箱内空间和资源减少, 水箱构成一个高度竞争的微生态系统, 而竞争和隔离对居住其中的纤毛虫物种的形成和分化起到了重要作用(Durán-Ramírez et al., 2015).目前在水箱凤梨中已发现170种纤毛虫, 其中16种为水箱特有种(Durán- Ramírez et al., 2020).水箱凤梨在两栖动物这类易受干旱影响的小型脊椎动物演化过程中扮演了决定性的角色, 为适应水箱内部构造, 一些蝌蚪特化出异常纤细的身体, 以适应紧密重叠的凤梨叶基构成的狭窄空间(Benzing & Bennett, 2000).部分仅生活在水箱之中的蝾螈为了适应水箱内部环境, 特化出较小的躯干(约50 mm长), 细长的尾及四肢, 分开的趾以及正面定向的眼睛(Ruano-Fajardo et al., 2014). ...

Signatures of autogenic epiphyte succession for an aspen chronosequence

1

2013

... 林冠群落的演替是林冠学中的一个新兴研究方向, 当前研究较为透彻的是附生地衣的演替(Ellis & Ellis, 2013), 然而关于附生植物(特别是维管植物)是否存在演替现象还具有较大争议, 争议的核心在于附生植物是否可以被看做独立的群落.Mendieta- Leiva等(2015)认为附生植物在林冠中的分布普遍处于低密度状态, 彼此间的相互作用较少, 不符合组成群落的要求, 所以视为一种植物集群.而Woods等(2017)认为附生植物的演替在内冠之中(距树干2 m范围内)遵循替代模型, 而在整个林冠的角度上遵循积累模型.即宿主植物的幼年时期郁闭度较低, 该阶段通常是较为耐旱型的附生植物生长于内冠中, 如水龙骨科等; 随宿主的生长, 冠层内郁闭度逐渐上升, 中期阶段内冠出现了以兰科为代表的类群; 当宿主发育成熟, 冠层内环境趋于稳定时, 内冠通常被大型蕨类占据, 而前期和中期的附生物种并没有因此消失, 而是向冠层外围转移了, 因此小树上的附生植物种类通常是大树的子集(Woods et al., 2015). ...

Loss of foundation species: consequences for the structure and dynamics of forested ecosystems

1

2005

... 森林生态系统中, 高大乔木作为初级基础物种塑造了最初的物理结构框架, 改善了环境和生物胁迫源(Ellison et al., 2005).在此基础上, 由地表以上所有植物枝叶集合组成的林冠, 凭借垂直分层的三维结构, 为动植物提供了更多生存空间以及多样化的生态位(刘文耀等, 2006), 支持了大约40%的陆栖生物物种, 其中10%是林冠专有类群(Ozanne et al., 2003).对植物而言, 林冠环境有相对充足的阳光, 但由于无法获得土壤水, 时常会遭受间断性缺水的影响(Helbsing et al., 2000), 水分成为限制植物向林冠扩张的主要因素(Gentry & Dodson, 1987).随着收集叶、肉质叶、肉质茎、景天酸代谢(CAM)等一系列适应对策的出现(Zotz et al., 2020), 使诸如兰科、凤梨科、薄囊蕨纲等附生维管植物类群(后文简称附生植物)得以在其他植物体表面附着生长, 并在生命的所有阶段依赖于其他植物体的结构支撑(Zotz, 2016).附生植物向林冠的扩张极大地开拓了附生植物的生存空间, 与林冠生物群的相互作用促使了更多特化生态位的出现, 致使附生植物快速分化, 拥有极高的物种多样性(Gamisch et al., 2021; Zotz et al., 2021). ...

Doubling the estimate of invertebrate biomass in a rainforest canopy

1

2004

... 篮式植物在林冠中重建了一个类似地表的高位土环境(Ortega-Solis et al., 2021), 在满足自身养分与水分需求的同时, 为林冠多种生物营建了理想的生境(Beaulieu et al., 2010).许多动物的生长、繁殖都会依赖篮式植物营建的生境(Phillips et al., 2020), 已记录有15纲97科的动物居住于各类篮式植物中, 其中有90科都是无脊椎动物.以鸟巢蕨为例, 加里曼丹岛热带森林中, 林冠中几乎一半的无脊椎动物生物量汇聚于鸟巢蕨中(Ellwood & Foster, 2004), 在日本南部亚热带森林的研究表明, 鸟巢蕨提升了当地无脊椎动物丰度, 并可以为特定物种提供生境, 有助于在亚热带森林尺度上保持无脊椎动物的高物种多样性(Karasawa & Hijii, 2006).除无脊椎动物之外, 鸟巢蕨是蛙类在林冠中重要的生境, 在吕宋岛南部有近1/5的鸟巢蕨被蛙类利用, 尤其是在白天高温之下, 鸟巢蕨的温、湿度的缓冲能力为蛙类创造了理想的避暑空间, 同时潮湿凉爽的内部环境也是蛙类重要的繁殖场所(Scheffers et al., 2014b).在加里曼丹岛人工安置的32株鸟巢蕨中, 半年后均记录到爬行纲的半叶趾虎(Hemiphyllodactylus typus)及Lipinia vittigera在其中栖息并产卵(Donald et al, 2017b).对哺乳动物来说, 鸟巢蕨是东南亚地区斑翅果蝠(Balionycteris maculata)搭建繁殖巢的理想场所, 增加了果蝠的繁殖成功率(Hodgkison et al., 2003). ...

The effect of rain forest canopy architecture on the distribution of epiphytic ferns (Asplenium spp.) in Sabah, Malaysia

1

2009

... 巢蕨(Asplenium nidus)及其近缘物种组成的鸟巢蕨类植物是最具代表性的篮式植物(图1A), 受关注度也最高.鸟巢蕨广泛分布于旧热带地区(Fayle et al., 2009), 每株鸟巢蕨可捕获0.1-20 kg干质量的碎屑(Ortega-Solis et al., 2021), 腐化形成的高位土pH呈酸性, 有机质及氮、磷、钾含量均高于地表土壤(徐诗涛, 2013).同时, 鸟巢蕨的海绵状根有极强的吸水能力, 加之叶片的遮阴作用, 使其对温度、湿度的变化具有一定的缓冲能力(Turner & Foster, 2006), 能在8-13天持续干燥环境中保持30%以上的水分(Scheffers et al., 2014a). ...

Facultative ant association benefits a Neotropical orchid

1

1992

... 新热带区的兰科的Caularthron、Myrmecophila、Schomburgkia和Dimerandra等属植物, 其部分假鳞茎会自然发育成内部中空, 仅在基部留有一个开口的形态, 以适宜蚂蚁居住(Fisher et al., 1990) (图1D).这些植物能够收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑并从碎屑中获得氮素(Gegenbauer et al., 2012), 有蚂蚁居住的植株可获得更加充足的养分, 产生更多的芽和果(Fisher, 1992).而为了更大限度地吸引蚂蚁前来居住, 兰科植物还常常提供花外蜜作为蚂蚁的食物(Fisher & Zimmerman, 1988).南美洲的Microgramma bifrons通过演化出中空的囊状侧根吸引蚂蚁居住(Davidson & Epstein, 1989).凤梨科Tillandsia属植物在加宽的叶基之间有空腔, 蚂蚁可以通过穿孔方式进入这些空腔定居(Benzing, 1970). ...

Variation in the use of orchid extrafloral nectar by ants

3

1990

... Representative families, genera, distribution and the specialized organs of ant-house epiphytes

Table 4 | 科 Family | 属 Genus | 特化器官 Specialized organ | 分布地 Distribution | 参考文献 Reference |

茜草科

Rubiaceae | Myrmecodia | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Kapitany, 2008 |

| Hydnophytum | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Kapitany, 2008 |

| Squamellaria | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 大洋洲

Oceania | Chomicki & Renner, 2019 |

夹竹桃科

Apocynaceae | 眼树莲属 Dischidia | 特化叶

Special leaves | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Treseder et al., 1995 |

水龙骨科

Polypodiaceae | Lecanopteris | 中空根状茎

Hollow rhizome | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Gay, 1991 |

兰科

Orchidaceae | 鹿角蕨属 Platycerium | 叶包鞘

Leaf sheath | 东南亚

Southeast Asia | Franken & Roos, 1982 |

| Microgramma | 中空的侧根状囊

Hollow lateral root sac | 南美洲

South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| Caularthron | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Fisher et al., 1990 |

凤梨科

Bromeliaceae | Myrmecophila | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Fisher et al., 1990 |

| Schomburgkia | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Rico-Gray & Thien, 1989 |

| Dimerandra | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Stuntz et al., 2002 |

| Tillandsia | 叶基部扩宽

Leaf base widening | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Benzing, 1970 |

2 附生植物生境营建作用的生态学功能 2.1 提升生态系统物种多样性附生植物营建的生境对生态系统物种多样性具有积极影响, 收集型植物及其收集物在林冠中营建了难能可贵的类地表环境, 为诸多无法适应林冠暴晒、缺水等逆境的生物提供了必要的生境(Ortega- Solís et al, 2017).分布广泛的收集型植物及其营建的特殊生境在不同大洲的热带地区发挥着相似的生态功能, 支持了各地区生物类群在林冠中的生存.多项研究均指出, 收集型植物是局域尺度上非常重要的伞护种(umbrella species), 在生物多样性保护、生态过程和生态系统生态学研究中具有重要的意义, 值得加强研究和保护(Karasawa & Hijii, 2006; Phillips et al., 2020). ...

... .,

1990 | Schomburgkia | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Rico-Gray & Thien, 1989 |

| Dimerandra | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Stuntz et al., 2002 |

| Tillandsia | 叶基部扩宽

Leaf base widening | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Benzing, 1970 |

2 附生植物生境营建作用的生态学功能 2.1 提升生态系统物种多样性附生植物营建的生境对生态系统物种多样性具有积极影响, 收集型植物及其收集物在林冠中营建了难能可贵的类地表环境, 为诸多无法适应林冠暴晒、缺水等逆境的生物提供了必要的生境(Ortega- Solís et al, 2017).分布广泛的收集型植物及其营建的特殊生境在不同大洲的热带地区发挥着相似的生态功能, 支持了各地区生物类群在林冠中的生存.多项研究均指出, 收集型植物是局域尺度上非常重要的伞护种(umbrella species), 在生物多样性保护、生态过程和生态系统生态学研究中具有重要的意义, 值得加强研究和保护(Karasawa & Hijii, 2006; Phillips et al., 2020). ...

... 新热带区的兰科的Caularthron、Myrmecophila、Schomburgkia和Dimerandra等属植物, 其部分假鳞茎会自然发育成内部中空, 仅在基部留有一个开口的形态, 以适宜蚂蚁居住(Fisher et al., 1990) (图1D).这些植物能够收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑并从碎屑中获得氮素(Gegenbauer et al., 2012), 有蚂蚁居住的植株可获得更加充足的养分, 产生更多的芽和果(Fisher, 1992).而为了更大限度地吸引蚂蚁前来居住, 兰科植物还常常提供花外蜜作为蚂蚁的食物(Fisher & Zimmerman, 1988).南美洲的Microgramma bifrons通过演化出中空的囊状侧根吸引蚂蚁居住(Davidson & Epstein, 1989).凤梨科Tillandsia属植物在加宽的叶基之间有空腔, 蚂蚁可以通过穿孔方式进入这些空腔定居(Benzing, 1970). ...

Ant/orchid associations in the Barro Colorado national monument, Panama

1

1988

... 新热带区的兰科的Caularthron、Myrmecophila、Schomburgkia和Dimerandra等属植物, 其部分假鳞茎会自然发育成内部中空, 仅在基部留有一个开口的形态, 以适宜蚂蚁居住(Fisher et al., 1990) (图1D).这些植物能够收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑并从碎屑中获得氮素(Gegenbauer et al., 2012), 有蚂蚁居住的植株可获得更加充足的养分, 产生更多的芽和果(Fisher, 1992).而为了更大限度地吸引蚂蚁前来居住, 兰科植物还常常提供花外蜜作为蚂蚁的食物(Fisher & Zimmerman, 1988).南美洲的Microgramma bifrons通过演化出中空的囊状侧根吸引蚂蚁居住(Davidson & Epstein, 1989).凤梨科Tillandsia属植物在加宽的叶基之间有空腔, 蚂蚁可以通过穿孔方式进入这些空腔定居(Benzing, 1970). ...

Direct and indirect effects of Tillandsia recurvata on Prosopis laevigata in the Chihuahua Desert scrubland of San Luis Potosi, Mexico

1

2014

... 相较于动物间的互作, 附生植物与其他植物间的互作关系更难以被观察, 其机理大多涉及生理层面的反应, 且作用周期较长.关于林冠植物间的相互作用研究还不透彻, 很多观点还存在争议, 其中之一就是附生植物与宿主植物间的关系问题.部分研究认为附生植物的存在会影响降雨的再分配, 提升宿主的水分利用效率(Mendieta-Leiva et al., 2015),一些宿主树种可以在它们所支撑的附生植物有机质层下形成不定根网络来获取其中的养分(Nadkarni, 1981).而相反的研究则认为附生植物的大量生长会对宿主韧皮部和木质部产生机械性损伤, 收集型附生植物私有化的枯枝落叶是对宿主养分的掠夺, 因此宿主通常会采取化感作用抑制附生植物萌发或是频繁脱落树皮以摆脱附生植物(Spicer & Woods, 2022), 而一些凤梨科植物的凋落物中甚至含有抑制宿主幼苗萌发的化学物质(Flores-Palacios et al., 2014), 使得附生植物与宿主间的关系更加复杂化.总体而言, 一些观察性结论可能带有偏差进而影响实验结果, 如基于枯老的树干上存在更多附生植物推断附生植物对宿主造成损伤.附生植物与宿主间的相互作用受两者物种种类, 附生植物的丰度、功能组成、空间分布, 降水频率和强度, 气候带和生态系统类型等因素综合影响, 相互作用的类型和程度有所不同, 因此不能一概而论.现阶段附生植物与宿主相互作用的研究主要集中在热带区域, 完善亚热带地区的相关研究有利于深入了解两者间的作用方式与强度随纬度变化的格局. ...

Habitat isolation changes the beta diversity of the vascular epiphyte community in lower montane forest, Veracruz, Mexico

1

2008

... 在社会经济发展的趋势之下, 人类不可避免地需要将更多土地资源用于农业等方面的开发, 导致原始森林被逐渐吞噬.而附生植物高度依赖连续完整且冠层发育良好的原始森林提供生存场所, 土地利用方式的改变成为附生植物最严重的威胁(Flores- Palacios & García-Franco, 2008).目前, 以兰科为代表的很多附生植物都面临着生境丧失或是生境破碎化的风险(李大程等, 2022), 与连续生境相比, 破碎化生境中繁殖的植物后代表现出整体性的遗传冲刷, 削弱了它们应对环境变化的能力, 从而增加了灭绝的风险(Aguilar et al., 2019), 同时传粉者丧失进一步加剧了近亲繁殖和遗传漂变的危害. ...

Endemic ciliates (Protozoa, Ciliophora) from tank bromeliads (Bromeliaceae): a combined morphological, molecular, and ecological study

2

2003

... 不同水箱凤梨的贮水池之间具有不同的理化特性, 甚至含有某些特定物质, 由此产生的生境异质性, 提升了所庇护的原生生物和小型后生动物类群的多样性(Foissner et al., 2003).原生生物纤毛虫(Ciliophora spp.)是生态系统中参与营养循环和控制细菌种群的重要组成部分, 水箱凤梨为纤毛虫提供了一个林冠之上广泛分布的生存空间(Foissner et al., 2003).由于干旱时期水箱内空间和资源减少, 水箱构成一个高度竞争的微生态系统, 而竞争和隔离对居住其中的纤毛虫物种的形成和分化起到了重要作用(Durán-Ramírez et al., 2015).目前在水箱凤梨中已发现170种纤毛虫, 其中16种为水箱特有种(Durán- Ramírez et al., 2020).水箱凤梨在两栖动物这类易受干旱影响的小型脊椎动物演化过程中扮演了决定性的角色, 为适应水箱内部构造, 一些蝌蚪特化出异常纤细的身体, 以适应紧密重叠的凤梨叶基构成的狭窄空间(Benzing & Bennett, 2000).部分仅生活在水箱之中的蝾螈为了适应水箱内部环境, 特化出较小的躯干(约50 mm长), 细长的尾及四肢, 分开的趾以及正面定向的眼睛(Ruano-Fajardo et al., 2014). ...

... ., 2003).由于干旱时期水箱内空间和资源减少, 水箱构成一个高度竞争的微生态系统, 而竞争和隔离对居住其中的纤毛虫物种的形成和分化起到了重要作用(Durán-Ramírez et al., 2015).目前在水箱凤梨中已发现170种纤毛虫, 其中16种为水箱特有种(Durán- Ramírez et al., 2020).水箱凤梨在两栖动物这类易受干旱影响的小型脊椎动物演化过程中扮演了决定性的角色, 为适应水箱内部构造, 一些蝌蚪特化出异常纤细的身体, 以适应紧密重叠的凤梨叶基构成的狭窄空间(Benzing & Bennett, 2000).部分仅生活在水箱之中的蝾螈为了适应水箱内部环境, 特化出较小的躯干(约50 mm长), 细长的尾及四肢, 分开的趾以及正面定向的眼睛(Ruano-Fajardo et al., 2014). ...

Earthworms inhabiting bromeliads in Mexican tropical rainforests: ecological and historical determinants

1

1996

... Bromeliads plants with tank structure and animals living inside

Table 2 亚科

Subfamily | 属

Genus | 分布

Distribution | 主要共存动物(纲)

Main coexisting fauna (class) | 参考文献

Reference |

沙漠凤梨亚科

Pitcairnioideae | Brocchinia | 南美洲 South America | P | Givnish et al.,1984 |

凤梨亚科

Bromelioideae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A-N, P-T | Freire et al., 2021 |

| Androlepis | 中美洲 Central America | F | Fragoso & Rojas-Fernández, 1996 |

| Araeococcus | 中美洲 Central America | P | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| 水塔花属 Billbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

| Canistrum | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Hohenbergia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Lymania | 中美洲 Central America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Neoregelia | 中美洲 Central America | A, I, M, P, Q, R | Almeida & Souza, 2020 |

| Ronnbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Nidularium | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

Invertebrate animals extracted from native tillandsia (Bromeliales: Bromeliaceae) in Sarasota County, Florida

1

2004

... Bromeliads plants with tank structure and animals living inside

Table 2 亚科

Subfamily | 属

Genus | 分布

Distribution | 主要共存动物(纲)

Main coexisting fauna (class) | 参考文献

Reference |

沙漠凤梨亚科

Pitcairnioideae | Brocchinia | 南美洲 South America | P | Givnish et al.,1984 |

凤梨亚科

Bromelioideae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A-N, P-T | Freire et al., 2021 |

| Androlepis | 中美洲 Central America | F | Fragoso & Rojas-Fernández, 1996 |

| Araeococcus | 中美洲 Central America | P | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| 水塔花属 Billbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

| Canistrum | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Hohenbergia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Lymania | 中美洲 Central America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Neoregelia | 中美洲 Central America | A, I, M, P, Q, R | Almeida & Souza, 2020 |

| Ronnbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Nidularium | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

The first record of Platycerium ridleyi in Sumatera

2

1982

... Representative families, genera, distribution and the specialized organs of ant-house epiphytes

Table 4 | 科 Family | 属 Genus | 特化器官 Specialized organ | 分布地 Distribution | 参考文献 Reference |

茜草科

Rubiaceae | Myrmecodia | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Kapitany, 2008 |

| Hydnophytum | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Kapitany, 2008 |

| Squamellaria | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 大洋洲

Oceania | Chomicki & Renner, 2019 |

夹竹桃科

Apocynaceae | 眼树莲属 Dischidia | 特化叶

Special leaves | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Treseder et al., 1995 |

水龙骨科

Polypodiaceae | Lecanopteris | 中空根状茎

Hollow rhizome | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Gay, 1991 |

兰科

Orchidaceae | 鹿角蕨属 Platycerium | 叶包鞘

Leaf sheath | 东南亚

Southeast Asia | Franken & Roos, 1982 |

| Microgramma | 中空的侧根状囊

Hollow lateral root sac | 南美洲

South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| Caularthron | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Fisher et al., 1990 |

凤梨科

Bromeliaceae | Myrmecophila | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Fisher et al., 1990 |

| Schomburgkia | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Rico-Gray & Thien, 1989 |

| Dimerandra | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Stuntz et al., 2002 |

| Tillandsia | 叶基部扩宽

Leaf base widening | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Benzing, 1970 |

2 附生植物生境营建作用的生态学功能 2.1 提升生态系统物种多样性附生植物营建的生境对生态系统物种多样性具有积极影响, 收集型植物及其收集物在林冠中营建了难能可贵的类地表环境, 为诸多无法适应林冠暴晒、缺水等逆境的生物提供了必要的生境(Ortega- Solís et al, 2017).分布广泛的收集型植物及其营建的特殊生境在不同大洲的热带地区发挥着相似的生态功能, 支持了各地区生物类群在林冠中的生存.多项研究均指出, 收集型植物是局域尺度上非常重要的伞护种(umbrella species), 在生物多样性保护、生态过程和生态系统生态学研究中具有重要的意义, 值得加强研究和保护(Karasawa & Hijii, 2006; Phillips et al., 2020). ...

... 在与蚂蚁共生的过程中, 蚁栖植物展现了极具创意性的演化方式.旧热带区茜草科的Myrmecodia与Hydnophytum植物通常生活在低海拔沿海养分贫瘠的环境(Kapitany, 2008).随植株的生长, 其下胚层逐渐扩大并发育出一系列复杂的内腔以营建适宜蚂蚁居住的环境(Volp & Lach, 2019), 内腔通道两旁排列着许多突起的内部根, 能够吸收水和溶解其中的营养物质(Rowe, 2012).蚂蚁入住后在通道内留下多种形式的有机碎屑, 碎屑中的养分最终被内部根吸收供给植物(Abdullah et al., 2017).夹竹桃科眼树莲属(Dischidia)植物通过特化部分叶片, 使其膨大中空, 形成囊状的蚂蚁叶(ant-leaves), 且腔壁上有气孔, 形成一个稳定可控的内部环境(Kapitany, 2008).随着蚂蚁的定居, 特化叶不断收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑, 同时产生不定根从基部开口处向叶内生长蔓延.通过稳定同位素分析表明, 宿主植物叶片中39%的碳来自蚂蚁相关的呼吸作用, 29%的氮来自沉积到蚂蚁叶中的有机碎屑(Treseder et al., 1995).水龙骨科Lecanopteris属植物拥有二型根状茎, 分为有叶着生的实心部分和无叶的空心部分, 空心部分为蚂蚁提供住所(Gay, 1991).使用15N同位素标记的饲养实验证明了蚂蚁活动产生的营养物质可以被Lecanopteris属植物吸收利用(Gay, 1991).鹿角蕨属(Platycerium)的P. ridleyi通过营养叶包裹隆起形成中空区域, 以适宜蚂蚁居住(Franken & Roos, 1982). ...

Review of the interactions of an ecological keystone species, Aechmea distichantha Lem. (Bromeliaceae), with the associated fauna

1

2021

... Bromeliads plants with tank structure and animals living inside

Table 2 亚科

Subfamily | 属

Genus | 分布

Distribution | 主要共存动物(纲)

Main coexisting fauna (class) | 参考文献

Reference |

沙漠凤梨亚科

Pitcairnioideae | Brocchinia | 南美洲 South America | P | Givnish et al.,1984 |

凤梨亚科

Bromelioideae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A-N, P-T | Freire et al., 2021 |

| Androlepis | 中美洲 Central America | F | Fragoso & Rojas-Fernández, 1996 |

| Araeococcus | 中美洲 Central America | P | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| 水塔花属 Billbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

| Canistrum | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Hohenbergia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Lymania | 中美洲 Central America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Neoregelia | 中美洲 Central America | A, I, M, P, Q, R | Almeida & Souza, 2020 |

| Ronnbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Nidularium | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

Evolution of crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) as an escape from ecological niche conservatism in Malagasy Bulbophyllum (Orchidaceae)

1

2021

... 森林生态系统中, 高大乔木作为初级基础物种塑造了最初的物理结构框架, 改善了环境和生物胁迫源(Ellison et al., 2005).在此基础上, 由地表以上所有植物枝叶集合组成的林冠, 凭借垂直分层的三维结构, 为动植物提供了更多生存空间以及多样化的生态位(刘文耀等, 2006), 支持了大约40%的陆栖生物物种, 其中10%是林冠专有类群(Ozanne et al., 2003).对植物而言, 林冠环境有相对充足的阳光, 但由于无法获得土壤水, 时常会遭受间断性缺水的影响(Helbsing et al., 2000), 水分成为限制植物向林冠扩张的主要因素(Gentry & Dodson, 1987).随着收集叶、肉质叶、肉质茎、景天酸代谢(CAM)等一系列适应对策的出现(Zotz et al., 2020), 使诸如兰科、凤梨科、薄囊蕨纲等附生维管植物类群(后文简称附生植物)得以在其他植物体表面附着生长, 并在生命的所有阶段依赖于其他植物体的结构支撑(Zotz, 2016).附生植物向林冠的扩张极大地开拓了附生植物的生存空间, 与林冠生物群的相互作用促使了更多特化生态位的出现, 致使附生植物快速分化, 拥有极高的物种多样性(Gamisch et al., 2021; Zotz et al., 2021). ...

Ant-houses in the fern genus Lecanopteris Reinw. (Polypodiaceae): the rhizome morphology and architecture of L. sarcopus Teijsm. & Binnend. and L. darnaedii Hennipman

3

1991

... Representative families, genera, distribution and the specialized organs of ant-house epiphytes

Table 4 | 科 Family | 属 Genus | 特化器官 Specialized organ | 分布地 Distribution | 参考文献 Reference |

茜草科

Rubiaceae | Myrmecodia | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Kapitany, 2008 |

| Hydnophytum | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Kapitany, 2008 |

| Squamellaria | 通道式块状茎

Channel tuberous stem | 大洋洲

Oceania | Chomicki & Renner, 2019 |

夹竹桃科

Apocynaceae | 眼树莲属 Dischidia | 特化叶

Special leaves | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Treseder et al., 1995 |

水龙骨科

Polypodiaceae | Lecanopteris | 中空根状茎

Hollow rhizome | 东南亚、大洋洲

Southeast Asia, Oceania | Gay, 1991 |

兰科

Orchidaceae | 鹿角蕨属 Platycerium | 叶包鞘

Leaf sheath | 东南亚

Southeast Asia | Franken & Roos, 1982 |

| Microgramma | 中空的侧根状囊

Hollow lateral root sac | 南美洲

South America | Davidson & Epstein, 1989 |

| Caularthron | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Fisher et al., 1990 |

凤梨科

Bromeliaceae | Myrmecophila | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Fisher et al., 1990 |

| Schomburgkia | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Rico-Gray & Thien, 1989 |

| Dimerandra | 中空假鳞茎

Hollow pseudobulb | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Stuntz et al., 2002 |

| Tillandsia | 叶基部扩宽

Leaf base widening | 中美洲、南美洲

Central, South America | Benzing, 1970 |

2 附生植物生境营建作用的生态学功能 2.1 提升生态系统物种多样性附生植物营建的生境对生态系统物种多样性具有积极影响, 收集型植物及其收集物在林冠中营建了难能可贵的类地表环境, 为诸多无法适应林冠暴晒、缺水等逆境的生物提供了必要的生境(Ortega- Solís et al, 2017).分布广泛的收集型植物及其营建的特殊生境在不同大洲的热带地区发挥着相似的生态功能, 支持了各地区生物类群在林冠中的生存.多项研究均指出, 收集型植物是局域尺度上非常重要的伞护种(umbrella species), 在生物多样性保护、生态过程和生态系统生态学研究中具有重要的意义, 值得加强研究和保护(Karasawa & Hijii, 2006; Phillips et al., 2020). ...

... 在与蚂蚁共生的过程中, 蚁栖植物展现了极具创意性的演化方式.旧热带区茜草科的Myrmecodia与Hydnophytum植物通常生活在低海拔沿海养分贫瘠的环境(Kapitany, 2008).随植株的生长, 其下胚层逐渐扩大并发育出一系列复杂的内腔以营建适宜蚂蚁居住的环境(Volp & Lach, 2019), 内腔通道两旁排列着许多突起的内部根, 能够吸收水和溶解其中的营养物质(Rowe, 2012).蚂蚁入住后在通道内留下多种形式的有机碎屑, 碎屑中的养分最终被内部根吸收供给植物(Abdullah et al., 2017).夹竹桃科眼树莲属(Dischidia)植物通过特化部分叶片, 使其膨大中空, 形成囊状的蚂蚁叶(ant-leaves), 且腔壁上有气孔, 形成一个稳定可控的内部环境(Kapitany, 2008).随着蚂蚁的定居, 特化叶不断收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑, 同时产生不定根从基部开口处向叶内生长蔓延.通过稳定同位素分析表明, 宿主植物叶片中39%的碳来自蚂蚁相关的呼吸作用, 29%的氮来自沉积到蚂蚁叶中的有机碎屑(Treseder et al., 1995).水龙骨科Lecanopteris属植物拥有二型根状茎, 分为有叶着生的实心部分和无叶的空心部分, 空心部分为蚂蚁提供住所(Gay, 1991).使用15N同位素标记的饲养实验证明了蚂蚁活动产生的营养物质可以被Lecanopteris属植物吸收利用(Gay, 1991).鹿角蕨属(Platycerium)的P. ridleyi通过营养叶包裹隆起形成中空区域, 以适宜蚂蚁居住(Franken & Roos, 1982). ...

... 属植物吸收利用(Gay, 1991).鹿角蕨属(Platycerium)的P. ridleyi通过营养叶包裹隆起形成中空区域, 以适宜蚂蚁居住(Franken & Roos, 1982). ...

Uptake of ant-derived nitrogen in the myrmecophytic orchid Caularthron bilamellatum

1

2012

... 新热带区的兰科的Caularthron、Myrmecophila、Schomburgkia和Dimerandra等属植物, 其部分假鳞茎会自然发育成内部中空, 仅在基部留有一个开口的形态, 以适宜蚂蚁居住(Fisher et al., 1990) (图1D).这些植物能够收集蚂蚁活动产生的有机碎屑并从碎屑中获得氮素(Gegenbauer et al., 2012), 有蚂蚁居住的植株可获得更加充足的养分, 产生更多的芽和果(Fisher, 1992).而为了更大限度地吸引蚂蚁前来居住, 兰科植物还常常提供花外蜜作为蚂蚁的食物(Fisher & Zimmerman, 1988).南美洲的Microgramma bifrons通过演化出中空的囊状侧根吸引蚂蚁居住(Davidson & Epstein, 1989).凤梨科Tillandsia属植物在加宽的叶基之间有空腔, 蚂蚁可以通过穿孔方式进入这些空腔定居(Benzing, 1970). ...

Diversity and biogeography of neotropical vascular epiphytes

1

1987

... 森林生态系统中, 高大乔木作为初级基础物种塑造了最初的物理结构框架, 改善了环境和生物胁迫源(Ellison et al., 2005).在此基础上, 由地表以上所有植物枝叶集合组成的林冠, 凭借垂直分层的三维结构, 为动植物提供了更多生存空间以及多样化的生态位(刘文耀等, 2006), 支持了大约40%的陆栖生物物种, 其中10%是林冠专有类群(Ozanne et al., 2003).对植物而言, 林冠环境有相对充足的阳光, 但由于无法获得土壤水, 时常会遭受间断性缺水的影响(Helbsing et al., 2000), 水分成为限制植物向林冠扩张的主要因素(Gentry & Dodson, 1987).随着收集叶、肉质叶、肉质茎、景天酸代谢(CAM)等一系列适应对策的出现(Zotz et al., 2020), 使诸如兰科、凤梨科、薄囊蕨纲等附生维管植物类群(后文简称附生植物)得以在其他植物体表面附着生长, 并在生命的所有阶段依赖于其他植物体的结构支撑(Zotz, 2016).附生植物向林冠的扩张极大地开拓了附生植物的生存空间, 与林冠生物群的相互作用促使了更多特化生态位的出现, 致使附生植物快速分化, 拥有极高的物种多样性(Gamisch et al., 2021; Zotz et al., 2021). ...

Choosing benefits or partners: a review of the evidence for the evolution of myrmecochory

1

2006

... 在降雨充沛的热带雨林, 蚂蚁用有机材料建造的树栖巢穴易受大雨冲刷解体, 为此蚂蚁会依靠种子上的化学信号将特定附生植物的种子带入巢中, 使附生植物在巢中扎根生长形成共生关系以此稳固蚁巢(图1C) (Kaufmann & Maschwitz, 2006).在这种共生关系中, 附生植物在蚂蚁的保护下安全萌发生长(Giladi, 2006), 富含有机质的蚁巢也能为植物提供充分的养分与水分; 而蚂蚁除了食用种子上的油质体等营养物质获得报酬外(黄曼和王东, 2015), 最重要的是依靠附生植物根系稳固蚁巢结构, 同时附生植物的叶也在很大程度上缓冲了暴雨对蚁巢的冲刷, 防止蚁巢解体(Yu, 1994). ...

Carnivory in the bromeliad Brocchinia reducta, with a cost/benefit model for the general restriction of carnivorous plants to sunny, moist, nutrient-poor habitats

1

1984

... Bromeliads plants with tank structure and animals living inside

Table 2 亚科

Subfamily | 属

Genus | 分布

Distribution | 主要共存动物(纲)

Main coexisting fauna (class) | 参考文献

Reference |

沙漠凤梨亚科

Pitcairnioideae | Brocchinia | 南美洲 South America | P | Givnish et al.,1984 |

凤梨亚科

Bromelioideae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A-N, P-T | Freire et al., 2021 |

| Androlepis | 中美洲 Central America | F | Fragoso & Rojas-Fernández, 1996 |

| Araeococcus | 中美洲 Central America | P | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| 水塔花属 Billbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

| Canistrum | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Hohenbergia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Lymania | 中美洲 Central America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Neoregelia | 中美洲 Central America | A, I, M, P, Q, R | Almeida & Souza, 2020 |

| Ronnbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Nidularium | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

Spider-fed bromeliads: seasonal and interspecific variation in plant performance

3

2011

... 旧热带区的鸟巢蕨是顶级无脊椎动物捕食者蜈蚣在林冠中的重要栖息场所, 仅从加里曼丹岛4株鸟巢蕨中就发现有305条蜈蚣居住(Phillips et al., 2020).而新热带区的凤梨科植物是顶级无脊椎动物捕食者蜘蛛觅食、交配、产卵及幼体成长的场所(Gonçalves et al., 2011).收集型植物影响了捕食性动物在林冠的分布和适合度, 进而凭借捕食者对其他动物的捕食, 间接调控着森林生态系统的食物网与群落结构, 被证明具有生态系统工程师作用(Rogy et al., 2019). ...

... 在庇护其他生物的过程中, 水箱凤梨也获得一定的回报, 水箱动物活动产生的排泄物以及尸体在丰富的微生物群的作用下快速分解(Leroy et al., 2016), 并最终被凤梨叶片的吸收性毛状体吸收利用(Leroy et al., 2019).有蛙类居住的水箱凤梨稳定氮同位素组成(δ15N)值显著高于无蛙类居住的个体(Romero et al., 2010), 部分水箱凤梨从蜘蛛获取的干物质氮含量占其总氮含量的2.4% ± 0.4% (Gonçalves et al., 2011).另一方面, 或许是因为水箱内部动物可提供丰富的有机物质, 加之微生物群的辅助分解为水箱凤梨提供了充足养分, 由此也促使水箱凤梨根部退化, 而叶片吸收性毛状体发达. ...

... 大部分附生植物生长速率缓慢, 植食性动物造成的叶片损伤会对植物产生极为不利的影响, 为此与蚂蚁或其他捕食动物的共生成为一种十分有利的防御手段.蚂蚁庞大的种群规模加上全年活动等特征是附生植物最理想的合作伙伴, 为蚂蚁提供栖息地是附生植物能长时间与蚂蚁建立联系并获取保护的重要方式.很多收集型植物能为多种捕食性动物营建适宜生境以获得保护, 如水箱凤梨内部蛙类以周边植食性节肢动物为食, 凤梨顶生高耸的花序也确保了这些蛙类不会吃掉潜在的传粉者(Sabagh et al., 2022), 此外各类蜘蛛与蚂蚁也为水箱凤梨提供了保护(Gonçalves et al., 2011).相比于凤梨科植物, 鸟巢蕨的叶片质薄, 长度可超过1 m, 理论上鸟巢蕨叶片更易受植食动物侵扰, 目前已知可为鸟巢蕨提供防御的生物类群有蚂蚁与蜈蚣(Woods, 2017; Phillips et al., 2020), 但它们大部分活动范围限于基部区域, 鸟巢蕨是否具有相关化学防御手段, 或与某些生物类群存在特定互作关系依然是一个值得探究的问题. ...

Cuticles of vascular epiphytes: efficient barriers for water loss after stomatal closure?

1

2000

... 森林生态系统中, 高大乔木作为初级基础物种塑造了最初的物理结构框架, 改善了环境和生物胁迫源(Ellison et al., 2005).在此基础上, 由地表以上所有植物枝叶集合组成的林冠, 凭借垂直分层的三维结构, 为动植物提供了更多生存空间以及多样化的生态位(刘文耀等, 2006), 支持了大约40%的陆栖生物物种, 其中10%是林冠专有类群(Ozanne et al., 2003).对植物而言, 林冠环境有相对充足的阳光, 但由于无法获得土壤水, 时常会遭受间断性缺水的影响(Helbsing et al., 2000), 水分成为限制植物向林冠扩张的主要因素(Gentry & Dodson, 1987).随着收集叶、肉质叶、肉质茎、景天酸代谢(CAM)等一系列适应对策的出现(Zotz et al., 2020), 使诸如兰科、凤梨科、薄囊蕨纲等附生维管植物类群(后文简称附生植物)得以在其他植物体表面附着生长, 并在生命的所有阶段依赖于其他植物体的结构支撑(Zotz, 2016).附生植物向林冠的扩张极大地开拓了附生植物的生存空间, 与林冠生物群的相互作用促使了更多特化生态位的出现, 致使附生植物快速分化, 拥有极高的物种多样性(Gamisch et al., 2021; Zotz et al., 2021). ...

Water-filled bromeliad as roost site of a tropical lizard, Urostrophus vautieri (Sauria: Leiosauridae)

1

2009

... Bromeliads plants with tank structure and animals living inside

Table 2 亚科

Subfamily | 属

Genus | 分布

Distribution | 主要共存动物(纲)

Main coexisting fauna (class) | 参考文献

Reference |

沙漠凤梨亚科

Pitcairnioideae | Brocchinia | 南美洲 South America | P | Givnish et al.,1984 |

凤梨亚科

Bromelioideae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A-N, P-T | Freire et al., 2021 |

| Androlepis | 中美洲 Central America | F | Fragoso & Rojas-Fernández, 1996 |

| Araeococcus | 中美洲 Central America | P | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| 水塔花属 Billbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

| Canistrum | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Hohenbergia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Lymania | 中美洲 Central America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Neoregelia | 中美洲 Central America | A, I, M, P, Q, R | Almeida & Souza, 2020 |

| Ronnbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Nidularium | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科

Tillandsioideae | Alcantarea | 中美洲 Central America | P, R | Henle & Knogge, 2009 |

| Mezobromelia | 南美洲 South America | P | Moyano & Benitez-Ortiz, 2013 |

| Catopsis | 中美洲 Central America | E, I, P, O, L, K, J | Nielsen, 2011 |

| Glomeropitcairnia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, P, Q | Jowers et al., 2008 |

| Guzmania | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P, Q, T | Torreias et al., 2010 |

| 铁兰属 Tillandsia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | I, K, M, N, P, H | Frank et al., 2004 |

| Vriesea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A, F, G, I, K, E, N, P, H, Q | Laviski et al., 2021 |

A, 线虫纲; B, 轮虫纲; C, 线形纲; D, 腹毛纲; E, 涡虫纲; F, 寡毛纲; G, 蛭纲; H, 腹足纲; I, 蛛形纲; J, 介形纲; K, 甲壳纲; L, 软甲纲; M, 唇足纲; N, 倍足纲; O, 弹尾纲; P, 昆虫纲; Q, 两栖纲; R, 爬行纲; S, 鸟纲; T, 哺乳纲; —, 无数据. ...

Roosting ecology and social organization of the spotted-winged fruit bat, Balionycteris maculata (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae), in a Malaysian lowland dipterocarp forest

1

2003

... 篮式植物在林冠中重建了一个类似地表的高位土环境(Ortega-Solis et al., 2021), 在满足自身养分与水分需求的同时, 为林冠多种生物营建了理想的生境(Beaulieu et al., 2010).许多动物的生长、繁殖都会依赖篮式植物营建的生境(Phillips et al., 2020), 已记录有15纲97科的动物居住于各类篮式植物中, 其中有90科都是无脊椎动物.以鸟巢蕨为例, 加里曼丹岛热带森林中, 林冠中几乎一半的无脊椎动物生物量汇聚于鸟巢蕨中(Ellwood & Foster, 2004), 在日本南部亚热带森林的研究表明, 鸟巢蕨提升了当地无脊椎动物丰度, 并可以为特定物种提供生境, 有助于在亚热带森林尺度上保持无脊椎动物的高物种多样性(Karasawa & Hijii, 2006).除无脊椎动物之外, 鸟巢蕨是蛙类在林冠中重要的生境, 在吕宋岛南部有近1/5的鸟巢蕨被蛙类利用, 尤其是在白天高温之下, 鸟巢蕨的温、湿度的缓冲能力为蛙类创造了理想的避暑空间, 同时潮湿凉爽的内部环境也是蛙类重要的繁殖场所(Scheffers et al., 2014b).在加里曼丹岛人工安置的32株鸟巢蕨中, 半年后均记录到爬行纲的半叶趾虎(Hemiphyllodactylus typus)及Lipinia vittigera在其中栖息并产卵(Donald et al, 2017b).对哺乳动物来说, 鸟巢蕨是东南亚地区斑翅果蝠(Balionycteris maculata)搭建繁殖巢的理想场所, 增加了果蝠的繁殖成功率(Hodgkison et al., 2003). ...

油质体在5种蚁播植物种子散布中的作用

1

2015

... 在降雨充沛的热带雨林, 蚂蚁用有机材料建造的树栖巢穴易受大雨冲刷解体, 为此蚂蚁会依靠种子上的化学信号将特定附生植物的种子带入巢中, 使附生植物在巢中扎根生长形成共生关系以此稳固蚁巢(图1C) (Kaufmann & Maschwitz, 2006).在这种共生关系中, 附生植物在蚂蚁的保护下安全萌发生长(Giladi, 2006), 富含有机质的蚁巢也能为植物提供充分的养分与水分; 而蚂蚁除了食用种子上的油质体等营养物质获得报酬外(黄曼和王东, 2015), 最重要的是依靠附生植物根系稳固蚁巢结构, 同时附生植物的叶也在很大程度上缓冲了暴雨对蚁巢的冲刷, 防止蚁巢解体(Yu, 1994). ...

油质体在5种蚁播植物种子散布中的作用

1

2015

... 在降雨充沛的热带雨林, 蚂蚁用有机材料建造的树栖巢穴易受大雨冲刷解体, 为此蚂蚁会依靠种子上的化学信号将特定附生植物的种子带入巢中, 使附生植物在巢中扎根生长形成共生关系以此稳固蚁巢(图1C) (Kaufmann & Maschwitz, 2006).在这种共生关系中, 附生植物在蚂蚁的保护下安全萌发生长(Giladi, 2006), 富含有机质的蚁巢也能为植物提供充分的养分与水分; 而蚂蚁除了食用种子上的油质体等营养物质获得报酬外(黄曼和王东, 2015), 最重要的是依靠附生植物根系稳固蚁巢结构, 同时附生植物的叶也在很大程度上缓冲了暴雨对蚁巢的冲刷, 防止蚁巢解体(Yu, 1994). ...

Ecological facilitation between two epiphytes through drought mitigation in a subtropical rainforest

1

2013

... 胁迫梯度假说预测了不同植物之间在低资源、高胁迫环境中更倾向于采取正相互作用以助于彼此的生存和繁殖(Bertness & Callaway, 1994).在林冠环境中, 附生植物之间的密切物理联系有利于改善干旱的胁迫, 因此在低密度状态下附生植物通常都表现出不同程度的互惠作用(Spicer & Woods, 2022), 如凤梨科交织的根系可以帮助捕捉其他附生植物随风传播的种子并有助于其萌发(Chaves & Rossatto, 2020); 大鳞巢蕨(A. antiquum)为附生在下方的Haplopteris zosterifolia提供了较为稳定的水分供给(Jian et al., 2013).随着附生植物密度的不断上升, 当达到某一临界值后种间关系可能由互惠转向竞争, 由于大多数附生植物在林冠中的分布都相对松散, 因此竞争是否会对附生植物多样性、丰度或群落聚集模式产生显著影响还存在争议(Spicer & Woods, 2022), 未来的研究应从更宏观且动态的角度进行探究, 依靠林冠塔吊等现代化科研设施, 对整个片区的附生植物进行长期监测, 分析附生植物的空间分布以及群落结构的动态变化, 以此探究附生植物种间种内各种形式的相互作用及其产生的影响. ...

The golden tree frog of Trinidad, Phyllodytes auratus (Anura: Hylidae): systematic and conservation status

1

2008

... Bromeliads plants with tank structure and animals living inside

Table 2 亚科

Subfamily | 属

Genus | 分布

Distribution | 主要共存动物(纲)

Main coexisting fauna (class) | 参考文献

Reference |

沙漠凤梨亚科

Pitcairnioideae | Brocchinia | 南美洲 South America | P | Givnish et al.,1984 |

凤梨亚科

Bromelioideae | Aechmea | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | A-N, P-T | Freire et al., 2021 |

| Androlepis | 中美洲 Central America | F | Fragoso & Rojas-Fernández, 1996 |

| Araeococcus | 中美洲 Central America | P | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| 水塔花属 Billbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

| Canistrum | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Hohenbergia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Lymania | 中美洲 Central America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Neoregelia | 中美洲 Central America | A, I, M, P, Q, R | Almeida & Souza, 2020 |

| Ronnbergia | 中美洲、南美洲 Central, South America | — | Benzing & Bennett, 2000 |

| Nidularium | 中美洲 Central America | P | Albertoni et al., 2016 |

| Quesnelia | 中美洲 Central America | P | Cardoso et al., 2015 |

空气凤梨亚科